“I was given three years to live. 28 years later, I’m still here.”

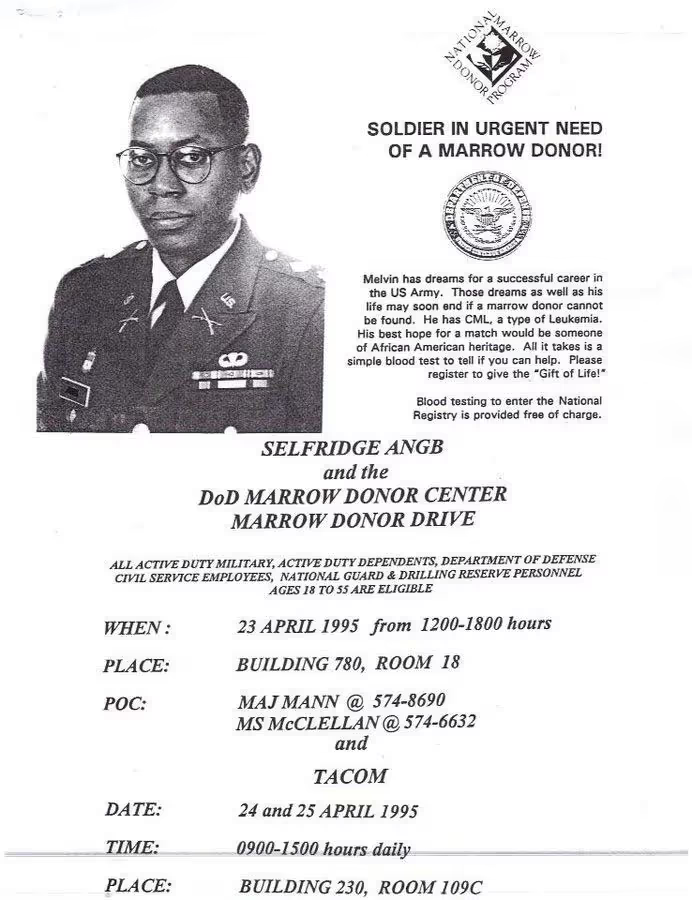

“I was commissioned into the Army when I graduated from college. My plan was to do 20 years, retire at 42, get another job, and then eventually retire from that one. But none of that materialized. The whole trajectory for my life changed. I was diagnosed with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) in 1995 and given three years to live. Yet 28 years later, I’m still here.

“I didn’t want to be a blurry memory to my daughter”

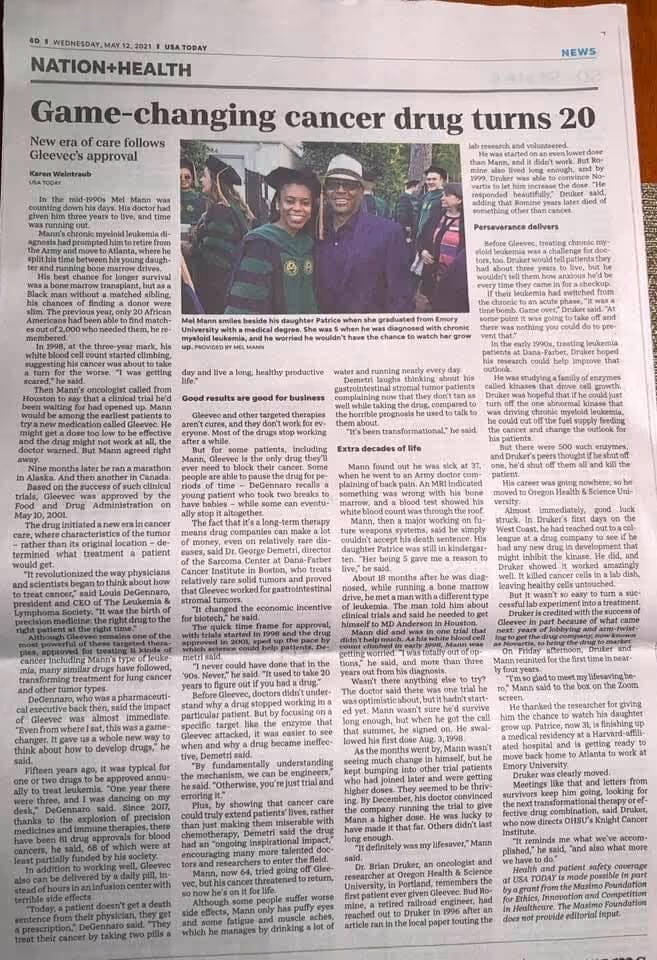

When I received my diagnosis, it was scary. Because it’s moments like that where, for the first time, it really sets in that you might not be here forever. My wife Cecelia and I were in our mid 30s when I was diagnosed. Not being here for my family is where most of my worry and emotion stemmed from. She was shocked when I told her.

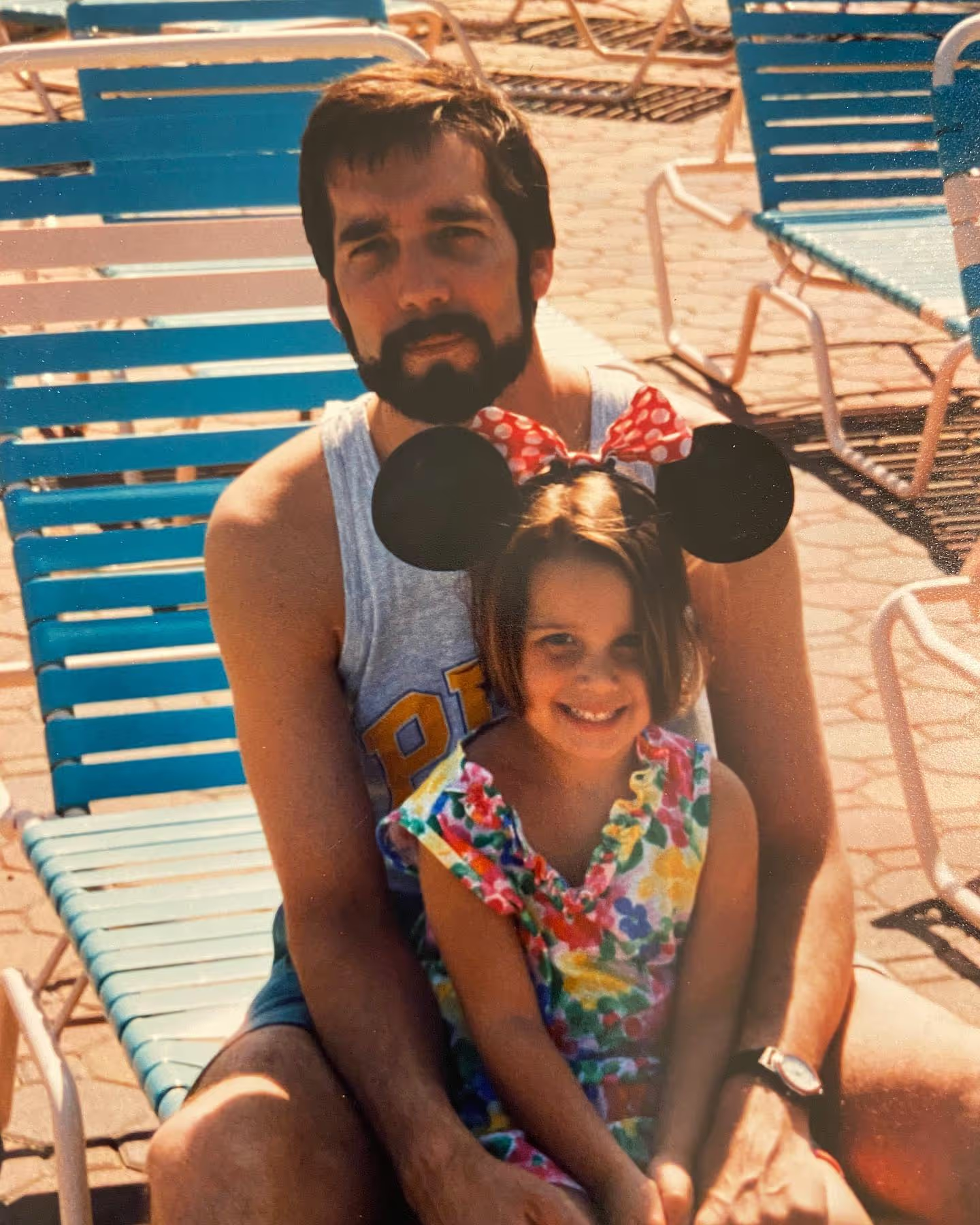

We told my daughter Patrice as much as we could given her age. She was five-years-old at the time, but she actually understood a lot of it. When the doctors told me I had three years to live, I thought of her, and was immediately counting how old she’d been when I reached the end of those three years. And then thought back to when I was that age, and remembered my grandmother died when I was in third grade…the exact same age. We have old pictures of my grandmother, but my memory of her is blurry. I knew I didn’t want to be a blurry memory to my daughter.

When I shared the news with my Mom, it was really hard on her. Because of course kids aren’t supposed to go before their parents. And my brother had passed in ‘91, just a few years prior. He was 15 years older than me. I was the baby of the family. I knew that losing another child would be really difficult. But ultimately, I feel blessed that I could tell her in person…that we weren’t distanced in the middle of a pandemic.

Ultimately, the emotional aspect of things turned out to be a good thing. Without those feelings, I’m not sure I would have fought as hard as I did. It’s what kept driving me.

“This was a real-life introduction to health disparities and the social determinants of health”

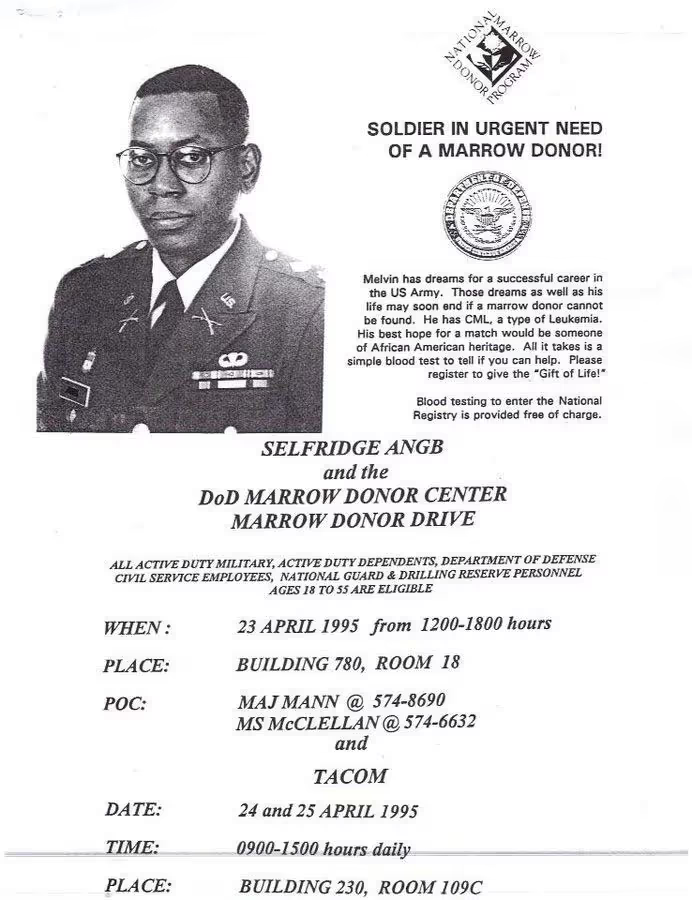

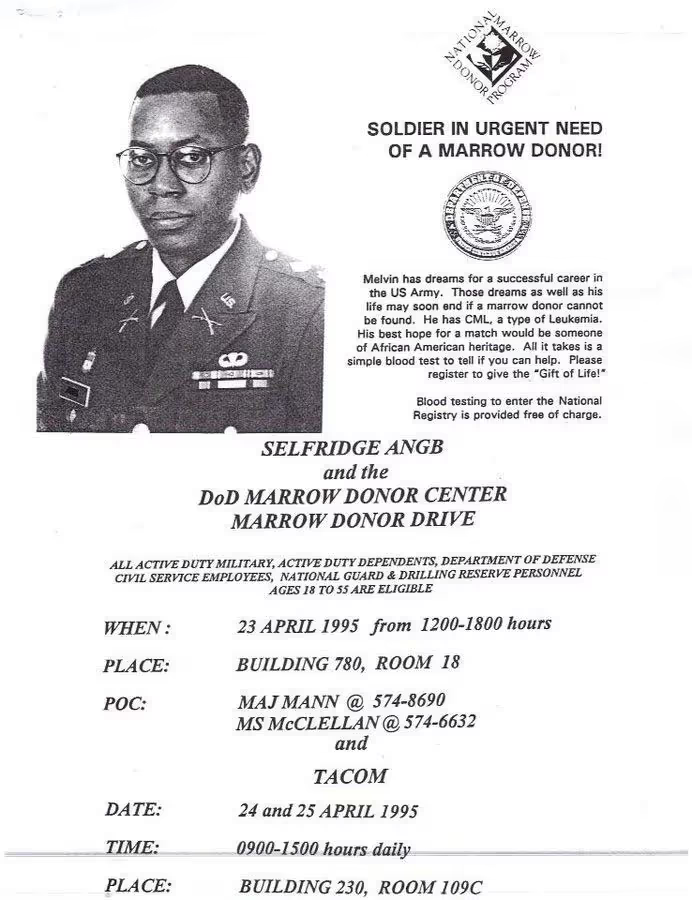

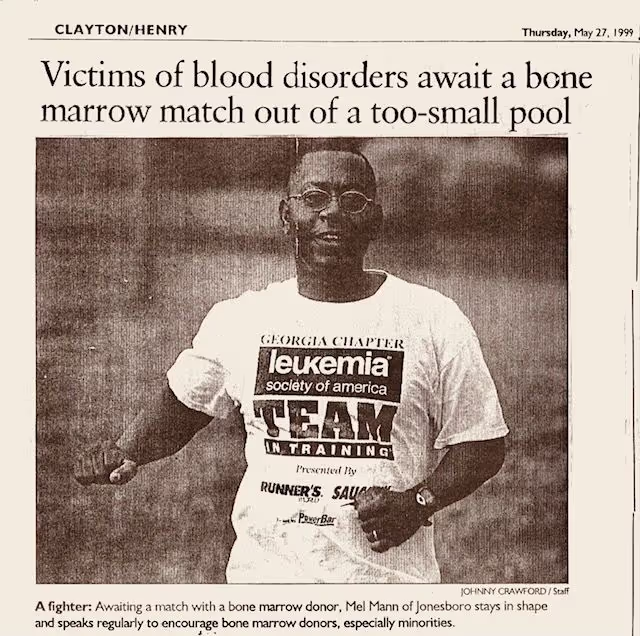

When I was diagnosed, I really hadn’t been sick my entire life. My medical record was like 1 page. I had great insurance through the military, but I didn’t really understand the healthcare system. I had poor health literacy. It wasn’t until my diagnosis - particularly when I was told that my only option was to find a bone marrow donor - where I started to understand the system better. My doctor told me that in 1994 (just one year prior) 2,000 African Americans needed bone marrow transplants, yet only 20 of them found life-saving donors. This was a real life introduction to health disparities and the social determinants of health.

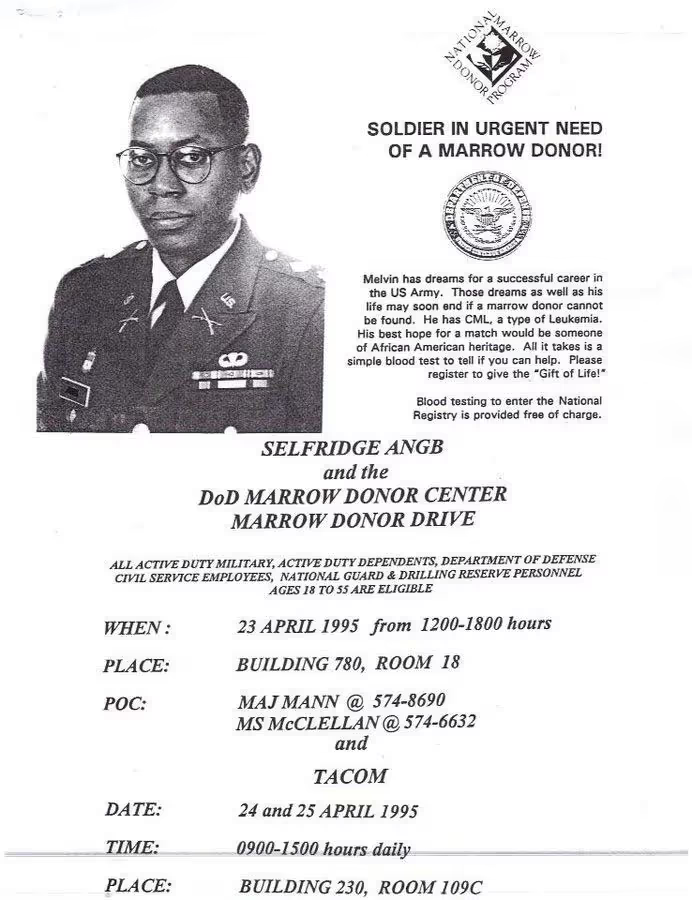

We held bone marrow drives on my base in Detroit, at the mall, in churches, and in other bases around the country. Our community really rallied around the cause. Officers and other co-workers helped organize the bone marrow drives and their spouses did refreshments. My military team managed drives in other parts of the world. Kids would come by our house to cut the grass. People even told me they’d have a pity party if I wanted one. I had such tremendous support from family, friends, the military, and the Church.

We worked really hard during those drives. It wasn’t easy. But I realized that so much of what I learned in the military was still relevant to these new challenges I was facing. I was able to use my military background to create recruitment strategies for the marrow registry, and figure out what would motivate someone to join. It also prepared me to face rejection a lot. When you’re asking people to do stuff, only a few of them will say yes. But you need to keep in mind that if you get 2/10, that’s excellent. So that mindset helped me with that. Somebody else who hadn’t already learned that life lesson may have felt discouraged by that number.

Education was a really important piece for me. Because if you don’t educate someone before they give a blood sample (or a cheek swab in more recent years), you could find out they are a match, only for them to end up not wanting to go through with donating stem cells or bone marrow. As a patient, it’s a really bad feeling when someone backs out right when you feel so close to being saved. And it happened frequently. Kids and teenagers would find matches, but the donors wouldn’t go through with it. So they died. I of course didn’t want that to happen, which is why I would really educate my friends. I would tell them, "If you’re going to join the registry, then you have to go through with it if you’re a match for someone. Don’t sign up if you’re not ready to see it through."

“It gave my life meaning”

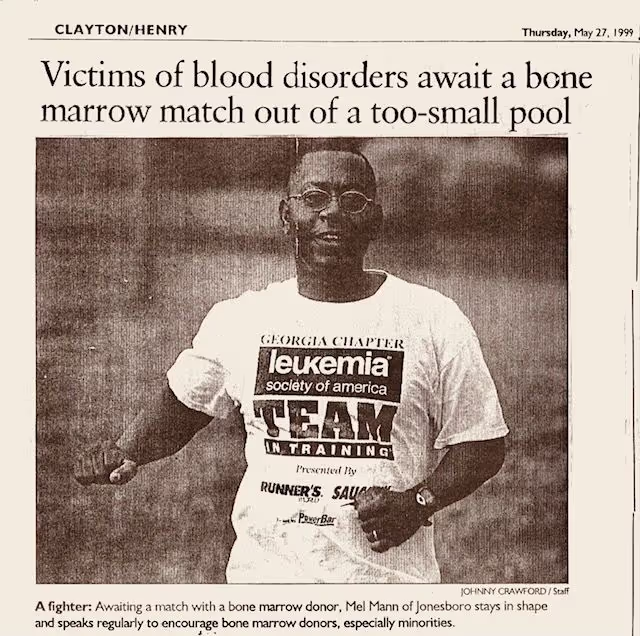

Over time, the odds of me finding a match weren’t promising. And there was still no approved drug available yet. But I still felt like this advocacy work had become my calling…that this is what I was supposed to be doing. It gave me another reason for living. It gave my life meaning. So I felt good about that. I’ll never forget receiving a phone call from a marrow donor representative in Detroit. I had just moved to Atlanta 6 months prior when she called. She said, “Remember that church drive we had with the two little girls, where only two people showed up? Well we just set a world record. 5,000 people came out for a little girl with leukemia.” This news felt really great. It felt like a movement, filled with people who each played their own important part of its success. I was just so glad to be part of it. The military was my entire life for so long…my advocacy work has sort of replaced that. And the number of donors at the drives only kept growing.

“16 months into my diagnosis, I learned about a clinical trial option for the first time”

When I was first diagnosed, I went to five different doctors. They all said the same thing…that I needed to find a bone marrow donor (which was abysmal, given that only around 1% of black folks who needed transplants found a donor). So I thought this was my fate.

But then, 16 months into my diagnosis, I learned about a clinical trial option for the first time. The guy who told me about it was at one of the bone marrow drives. He looked really in shape. I could tell he was an athlete. And it turns out he was an avid cyclist. He told me about his hairy cell leukemia diagnosis, and that he was near death before joining a clinical trial. He explained it all so vividly. I could visualize his experience, and even just looking at him in front of me, it gave me hope.

So I decided to travel to one of the clinical trial sites at MD Anderson in Houston. When I met my doctor, I discovered he was the first doctor to use interferon for CML, which was the first-line therapy at the time. He was one of the best in the world and was leading a trial for the current drug they were investigating for CML, and had also discovered a gradual improvement in efficacy for a different treatment. He carefully reviewed my records and said, “We still have time. I’m going to increase your dose of interferon and put you on clinical trial after clinical trial.”

This marked the first time I was informed of and asked to participate in a clinical trial. I realized then that I had experienced a 16-month delay of having an option to receive state-of-the-art medical treatment. It is often stated that some patients, especially some African Americans, are afraid they will be taken advantage of in clinical trials because of the past legacy of unethical experiments, including the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study. However, the reason may stem more from health inequities and lack of opportunities to participate in clinical trials for minorities. I saw clinical trials as a chance to get “tomorrow’s medicine, today.”

The doctors I had back in Atlanta were more traditional than the ones in Houston. They’d question why I even felt the need to go to MD Anderson. I didn’t know much about medicine, but I figured you never know. I knew what my other options were, and they weren’t good. So I thought perhaps maybe one of these other experimental drugs would work…or at least just keep me around longer. Eventually I decided to leave the military’s health system in Atlanta and completely took the civilian route in Houston, since those doctors, at the time, were more progressive. There have been some positive changes in the military’s health system since those years.

“It became a cycle of highs and lows”

The clinical trials I joined were hopeful, but it sort of became this cycle of highs and lows. The treatment would work for a period of time and then 30 days later it wouldn’t. So I’d feel happy and then disappointed, on repeat.

As I approached my three-year mark, the interferon as well as other experimental drugs had stopped working. I would wake up in the morning feeling like I never went to sleep. I was a lifelong runner. I remember looking out the hotel window at the Rotary House International at MD Anderson, thinking about going for a jog, but realizing that I couldn't jog even one city block.

Reading books became my new thing. I read a lot of books…like two per week. I joined book clubs. It played a big part in taking my mind somewhere else. I wanted to read about what motivated other people. I wanted to have more general knowledge. When I hit the three-year mark on my cancer journey, that’s when I started reading autobiographies of people who were in similar situations. The autobiography of Arthur Ash. Magic Johnson. Elizabeth Glaser. They all had AIDS, a fatal disease at that time. So I would read to get an understanding of their experience. Arthur Ash talks about hitting the life expectancy his doctors gave him, and how that felt. So that helped me cope. One woman at my book club even said something like, “You could go back to school with your GI Bill and major in literature! Read, get free books, all that good stuff!”

"It all came down to one final drug…and it was really close to my timeline"

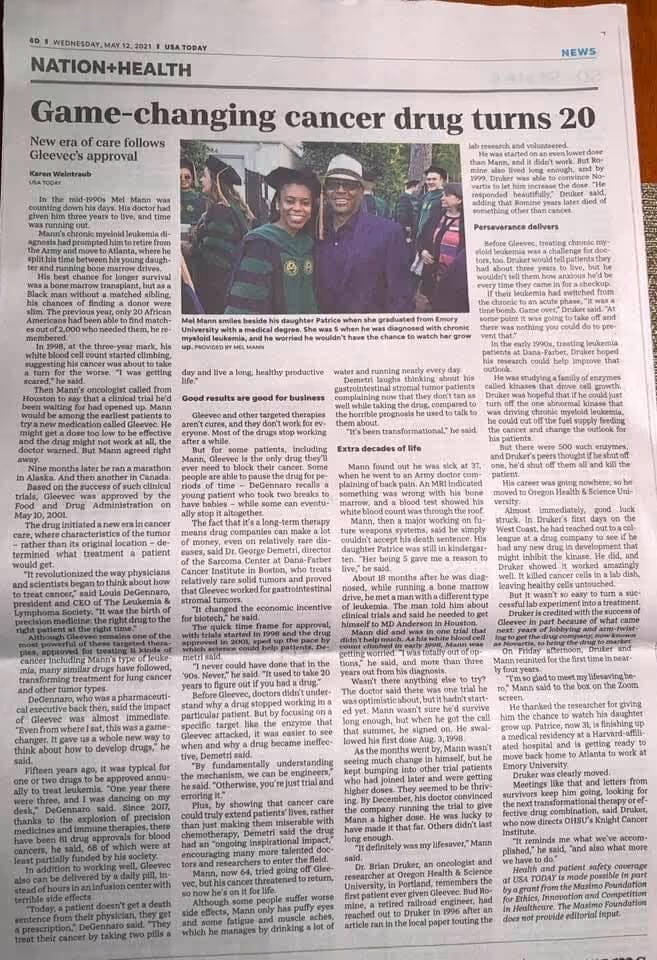

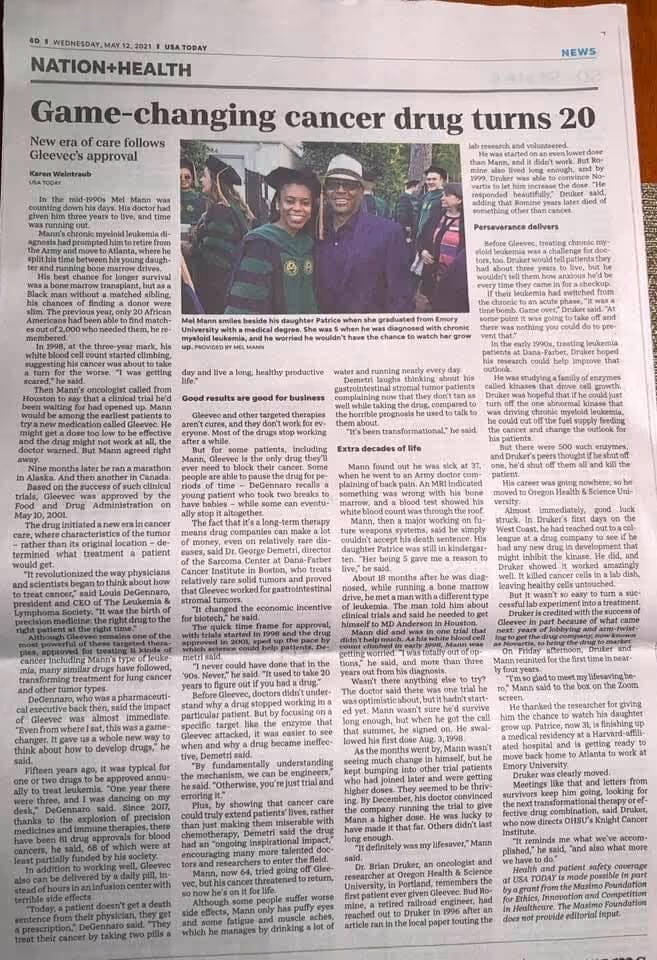

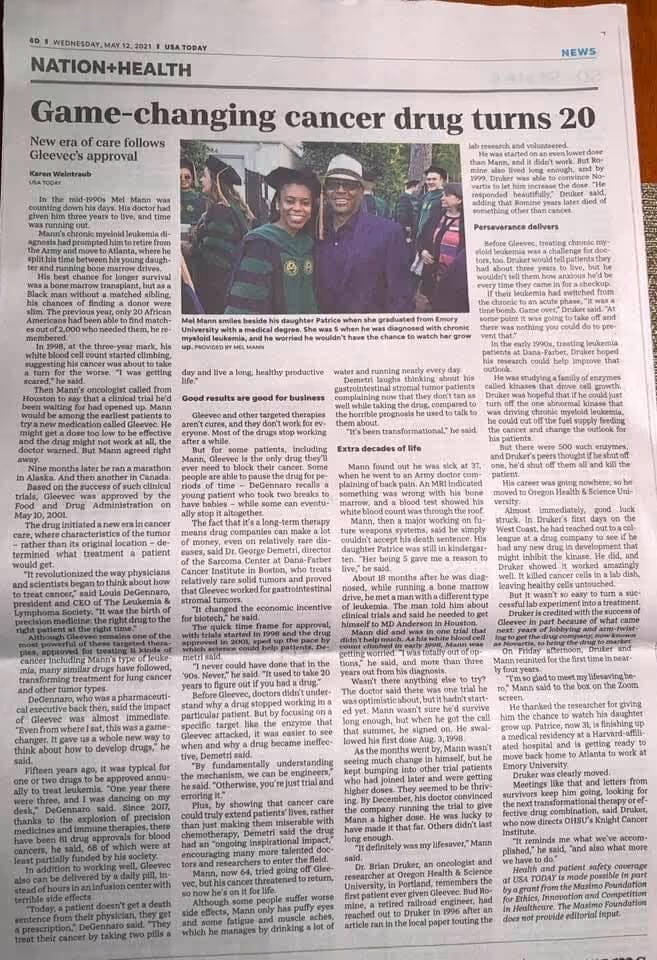

I hit my three-year mark, and then in August of 1998, MD Anderson got approval to start a phase 1 clinical trial on STI571 (Gleevec), led by Dr. Druker who was based in Oregon. I was the second person to receive this treatment at the clinical trial site at MD Anderson. There were three sites of about 20 patients each. The drug was working, but we didn’t know for how long. The doctors were basically gauging things in real time, as there was no predicting what would happen. They just didn’t understand the drug well enough yet.

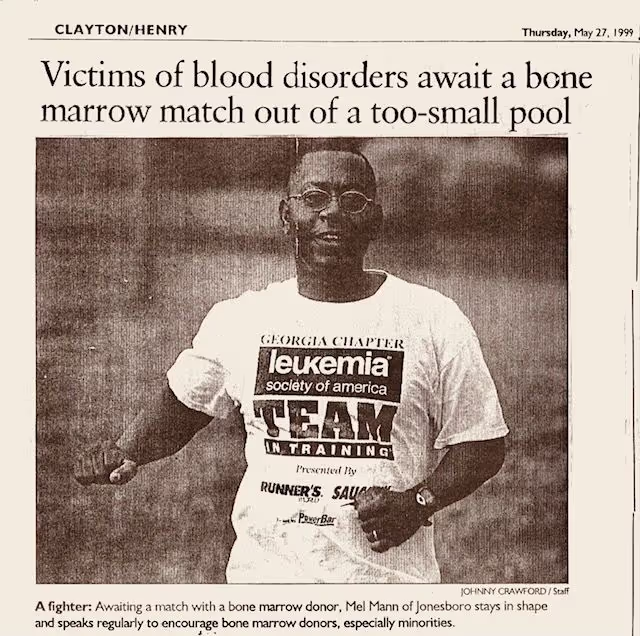

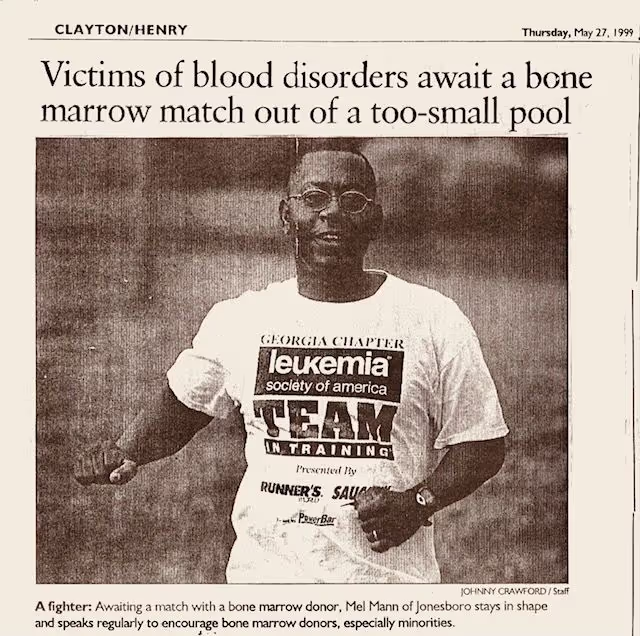

I ended up having amazing results with STI571, and the doctors said I’d probably have a pretty normal lifespan. In January 1999, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (LLS), who helped fund the trial contacted me and asked if I wanted to be something called a “patient hero.” They said some people would run a marathon in my honor and raise money for cancer research.

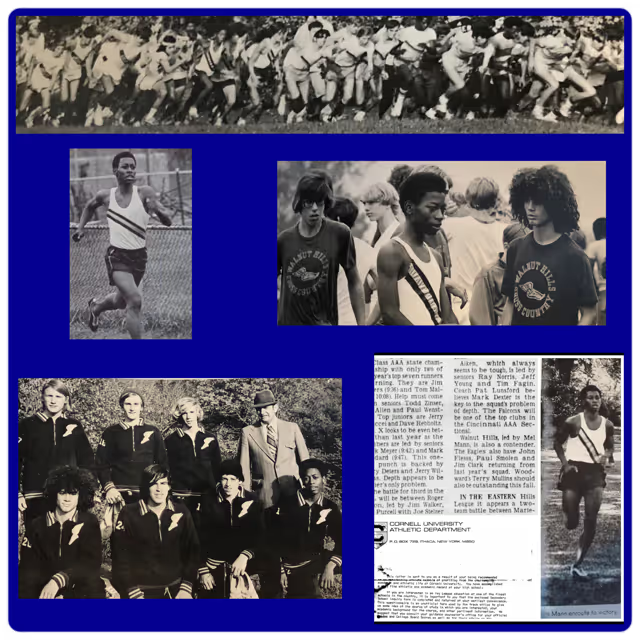

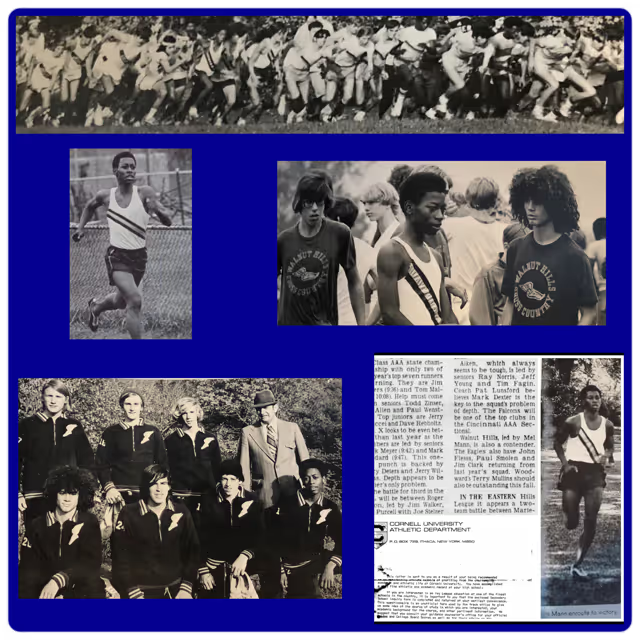

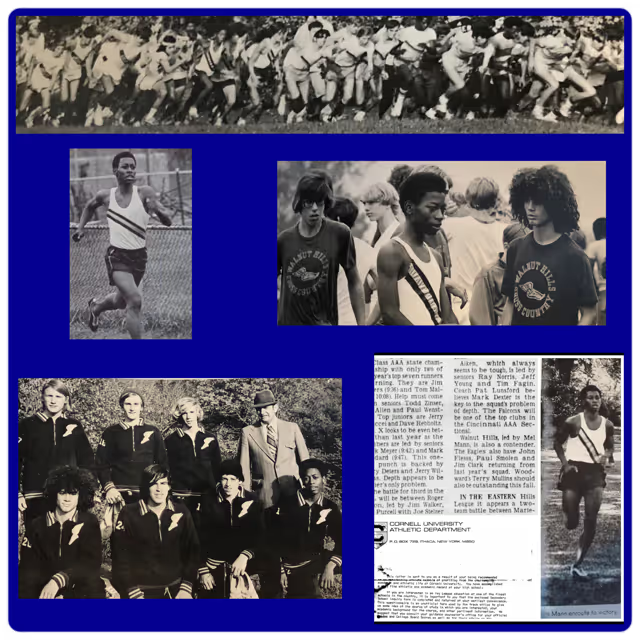

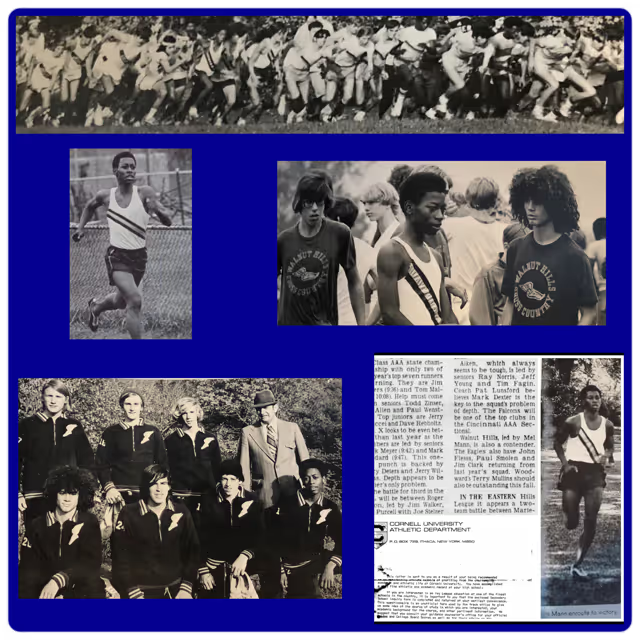

As I mentioned earlier, running has always been a huge part of my life. I had been the captain of my high school cross country and track teams. When I was 15 years old, I qualified for the Boston Marathon with 20 minutes to spare, despite having never ran more than eight miles in practice. Everyone was saying that my marathon time was one of the best times in the country for a sophomore. The only problem was, you had to be 18 years-old to run in the Boston Marathon. I was too young, so I never ran another marathon, and stayed with the shorter high school middle distances.

I had always wanted to do another marathon since that solo high school effort, but had never got back around to it. So when I was asked about being a patient hero, I pretty much knew my body and what was required to run a marathon, so I said, “I’ll do the patient hero marathon myself and raise the money also.” And that’s exactly what I did. MD Anderson received special approval to raise my dose to 250 mg daily, so my blood essentially returned to normal range. So much for my first oncologist’s advice, “Don’t run any marathons.”

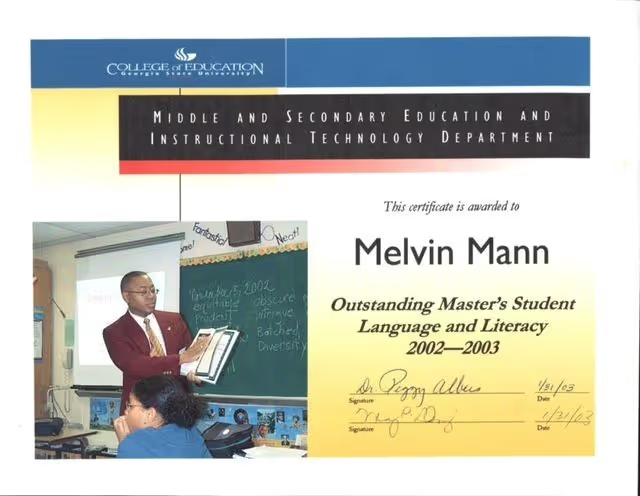

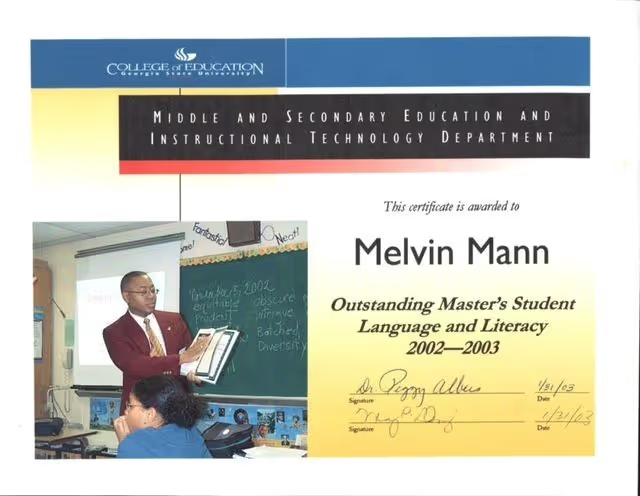

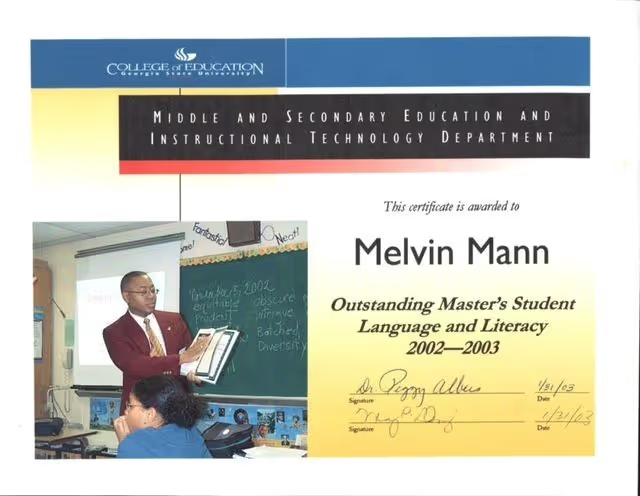

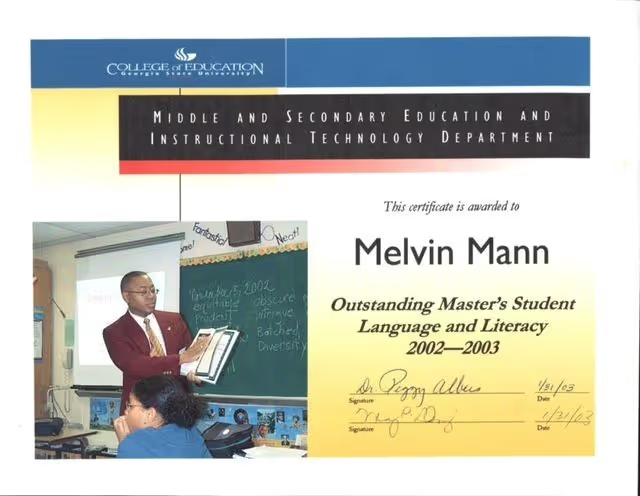

And then in January 2000, I took my book club friend’s advice and went back to school and received a BA in English Literature, an M.Ed. in Secondary English, and a license to teach. I still had military benefits, so they paid for it. The book club really motivated me.

“Before all of this, I was living every day with the next thing in mind”

In the military, you’re always kind of going for that next promotion. I was a Major, then almost Lieutenant Colonel. So I was moving up the ranks. But when I got the news of CML, all of that stuff just went out the window. My next promotion was the last thing on my mind. Since that day, time really seemed to start slowing down. I started to value it more. And that feeling stayed with me for a long time, even after I started on the drug. I felt like I could just experience things in slow motion. Just appreciate reading a book or whatever it was. Even though I was busy, I still appreciated time. I was very present. I was given three years to live, but I thought “Well, three years is a pretty long time!” Because I could have been given 1 year. That would have been more intense.

It did take me a while - maybe 10-15 years after I retired - to really integrate into the newness of being a “civilian.” Because when you’re in the military, it feels like 99% of your life. And then you think the civilian world is 1% of the actual world. But they say “Once you’re a soldier you’re a soldier for life.” So I still feel like a soldier, even after all these years.

“To me, it feels like a miracle”

The first miracle I was looking for was the bone marrow transplant. The drive organizers used to give out these cups that said “You’re going to find your miracle.” It was a risky procedure, given that back then you had a 50/50 chance of surviving the transplant, since transplants were still pretty new. I knew people who had a transplant and died. And many others opted to not pursue a transplant. “Better three years than six months,” they reasoned. But my daughter was only five years old, so I was willing to take the gamble.

I didn’t end up finding that miracle, but I found a different one that I didn’t see coming, thanks to clinical trials. Sometimes you’ve been in the throes of it for so long, that you almost forget to take a step back and reflect on it. But this journey has made me look at life in a way where I value things more. Because I was so close to not making it. A friend of mine, who was a child when he was diagnosed, was saying how if we had been diagnosed two or three years earlier, we wouldn’t be here. It’s just such a huge feeling of relief.

“This story is bigger than what we thought it was”

I started Gleevec in August 1998. At the time, it was not popular or well-known. No one was talking about it. But eventually as it showed more and more promise, people caught on. And people who started the drug many months after me were given credit for being the longest living survivors on Gleevec. I had been saying through the years that I was the longest living, but was ignored and dismissed. Other patients were featured in best-selling books and spoke on national and international panels about it. I was written out of history and became a hidden figure.

It was not until social media came along, sixteen years later in 2014, - when there were no gatekeepers - that my story really started to get picked up. I had built up my social media audience to half a million followers from some other things, like recruiting marrow donors over the internet, and interacting with the cancer community. So I posted some of my medical records, videos, newspaper clippings, etc. People actually got mad when I said I was the longest living and my medical records proved it. There was a lot of denial, even from some of the popular patient advocates & national organizations. It was kind of funny because I had never really seen another black patient in the very early part of the clinical trial, yet here I was, a black man - someone who wasn’t ‘supposed to be’ in clinical trials - and I had entered the trial before them and lived the longest. I was actually the first Black patient that I saw featured for CML that wasn’t a well-known celebrity.

My doctors changed a few times at MD Anderson. When I was asked to share my journey by MD Anderson and gave them my medical record number for my records they maintained, they said, “This story is bigger than what we thought it was.” And that’s when it kind of blew up. That’s when I started getting credit for being the longest living.

“Progress has been slow. Only 5% of clinical trial participants are black”

When we talk about progress in terms of awareness of and access to clinical trials for black people, there are two key barriers to address: 1) the fact that many people aren’t offered clinical trials to begin with (and therefore don’t even know it’s an option when they’re making a decision about their treatment) and 2) there’s a history of experimentation on the black body.

The travel cost has also been a big discriminator. Back in the early years of my treatment, I traveled back and forth for treatment every three months. I even lived in Houston for three months. That was just part of the protocol at the time. But a lot of people couldn’t afford that or take time off from work or from caring for their families and pets. But now because of the pandemic, people have realized that you don’t always have to travel for clinical trials. There’s a lot you can do right in your own city in terms of testing and things. I’m seeing a shift now where they’re trying to bring clinical trials closer to the patient. Because even for some people who live in a big city, if they are poor, trying to take the bus can still be a hassle.

Progress has been slow, but I’m seeing a ton of education about clinical trials to help people overcome fear. And that’s why I think my story is important, because you see a person who’s been on a clinical trial and you see the long-term survivor. If a clinical trial only buys someone another few months, people will ask if that’s worth it. But when they see someone who has survived five or ten more years, it becomes promising. It’s hard to dispute it because it worked. So patient stories are important, because patients going through it trust patients who have been through it (like I trusted the man who introduced me to clinical trials).

“We were on the front lines”

Today, getting a CML diagnosis is much different than it was back then. When I reminisce with other patients who were on the same trial as me, we know that we were on the front lines of a clinical trial that is now a standard treatment, and is saving the lives of patients who in the past were incurable."

Learn more about Mel’s story:

PBS Stories from the Stage: Living with Cancer (Aired: 06/05/23)

The Mel Mann Story: From Terminal Cancer to 28 Year Survivor

MD Anderson Video on how a Clinical Trial and Gleevec saved Mel Mann's life

“I was commissioned into the Army when I graduated from college. My plan was to do 20 years, retire at 42, get another job, and then eventually retire from that one. But none of that materialized. The whole trajectory for my life changed. I was diagnosed with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) in 1995 and given three years to live. Yet 28 years later, I’m still here.

“I didn’t want to be a blurry memory to my daughter”

When I received my diagnosis, it was scary. Because it’s moments like that where, for the first time, it really sets in that you might not be here forever. My wife Cecelia and I were in our mid 30s when I was diagnosed. Not being here for my family is where most of my worry and emotion stemmed from. She was shocked when I told her.

We told my daughter Patrice as much as we could given her age. She was five-years-old at the time, but she actually understood a lot of it. When the doctors told me I had three years to live, I thought of her, and was immediately counting how old she’d been when I reached the end of those three years. And then thought back to when I was that age, and remembered my grandmother died when I was in third grade…the exact same age. We have old pictures of my grandmother, but my memory of her is blurry. I knew I didn’t want to be a blurry memory to my daughter.

When I shared the news with my Mom, it was really hard on her. Because of course kids aren’t supposed to go before their parents. And my brother had passed in ‘91, just a few years prior. He was 15 years older than me. I was the baby of the family. I knew that losing another child would be really difficult. But ultimately, I feel blessed that I could tell her in person…that we weren’t distanced in the middle of a pandemic.

Ultimately, the emotional aspect of things turned out to be a good thing. Without those feelings, I’m not sure I would have fought as hard as I did. It’s what kept driving me.

“This was a real-life introduction to health disparities and the social determinants of health”

When I was diagnosed, I really hadn’t been sick my entire life. My medical record was like 1 page. I had great insurance through the military, but I didn’t really understand the healthcare system. I had poor health literacy. It wasn’t until my diagnosis - particularly when I was told that my only option was to find a bone marrow donor - where I started to understand the system better. My doctor told me that in 1994 (just one year prior) 2,000 African Americans needed bone marrow transplants, yet only 20 of them found life-saving donors. This was a real life introduction to health disparities and the social determinants of health.

We held bone marrow drives on my base in Detroit, at the mall, in churches, and in other bases around the country. Our community really rallied around the cause. Officers and other co-workers helped organize the bone marrow drives and their spouses did refreshments. My military team managed drives in other parts of the world. Kids would come by our house to cut the grass. People even told me they’d have a pity party if I wanted one. I had such tremendous support from family, friends, the military, and the Church.

We worked really hard during those drives. It wasn’t easy. But I realized that so much of what I learned in the military was still relevant to these new challenges I was facing. I was able to use my military background to create recruitment strategies for the marrow registry, and figure out what would motivate someone to join. It also prepared me to face rejection a lot. When you’re asking people to do stuff, only a few of them will say yes. But you need to keep in mind that if you get 2/10, that’s excellent. So that mindset helped me with that. Somebody else who hadn’t already learned that life lesson may have felt discouraged by that number.

Education was a really important piece for me. Because if you don’t educate someone before they give a blood sample (or a cheek swab in more recent years), you could find out they are a match, only for them to end up not wanting to go through with donating stem cells or bone marrow. As a patient, it’s a really bad feeling when someone backs out right when you feel so close to being saved. And it happened frequently. Kids and teenagers would find matches, but the donors wouldn’t go through with it. So they died. I of course didn’t want that to happen, which is why I would really educate my friends. I would tell them, "If you’re going to join the registry, then you have to go through with it if you’re a match for someone. Don’t sign up if you’re not ready to see it through."

“It gave my life meaning”

Over time, the odds of me finding a match weren’t promising. And there was still no approved drug available yet. But I still felt like this advocacy work had become my calling…that this is what I was supposed to be doing. It gave me another reason for living. It gave my life meaning. So I felt good about that. I’ll never forget receiving a phone call from a marrow donor representative in Detroit. I had just moved to Atlanta 6 months prior when she called. She said, “Remember that church drive we had with the two little girls, where only two people showed up? Well we just set a world record. 5,000 people came out for a little girl with leukemia.” This news felt really great. It felt like a movement, filled with people who each played their own important part of its success. I was just so glad to be part of it. The military was my entire life for so long…my advocacy work has sort of replaced that. And the number of donors at the drives only kept growing.

“16 months into my diagnosis, I learned about a clinical trial option for the first time”

When I was first diagnosed, I went to five different doctors. They all said the same thing…that I needed to find a bone marrow donor (which was abysmal, given that only around 1% of black folks who needed transplants found a donor). So I thought this was my fate.

But then, 16 months into my diagnosis, I learned about a clinical trial option for the first time. The guy who told me about it was at one of the bone marrow drives. He looked really in shape. I could tell he was an athlete. And it turns out he was an avid cyclist. He told me about his hairy cell leukemia diagnosis, and that he was near death before joining a clinical trial. He explained it all so vividly. I could visualize his experience, and even just looking at him in front of me, it gave me hope.

So I decided to travel to one of the clinical trial sites at MD Anderson in Houston. When I met my doctor, I discovered he was the first doctor to use interferon for CML, which was the first-line therapy at the time. He was one of the best in the world and was leading a trial for the current drug they were investigating for CML, and had also discovered a gradual improvement in efficacy for a different treatment. He carefully reviewed my records and said, “We still have time. I’m going to increase your dose of interferon and put you on clinical trial after clinical trial.”

This marked the first time I was informed of and asked to participate in a clinical trial. I realized then that I had experienced a 16-month delay of having an option to receive state-of-the-art medical treatment. It is often stated that some patients, especially some African Americans, are afraid they will be taken advantage of in clinical trials because of the past legacy of unethical experiments, including the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study. However, the reason may stem more from health inequities and lack of opportunities to participate in clinical trials for minorities. I saw clinical trials as a chance to get “tomorrow’s medicine, today.”

The doctors I had back in Atlanta were more traditional than the ones in Houston. They’d question why I even felt the need to go to MD Anderson. I didn’t know much about medicine, but I figured you never know. I knew what my other options were, and they weren’t good. So I thought perhaps maybe one of these other experimental drugs would work…or at least just keep me around longer. Eventually I decided to leave the military’s health system in Atlanta and completely took the civilian route in Houston, since those doctors, at the time, were more progressive. There have been some positive changes in the military’s health system since those years.

“It became a cycle of highs and lows”

The clinical trials I joined were hopeful, but it sort of became this cycle of highs and lows. The treatment would work for a period of time and then 30 days later it wouldn’t. So I’d feel happy and then disappointed, on repeat.

As I approached my three-year mark, the interferon as well as other experimental drugs had stopped working. I would wake up in the morning feeling like I never went to sleep. I was a lifelong runner. I remember looking out the hotel window at the Rotary House International at MD Anderson, thinking about going for a jog, but realizing that I couldn't jog even one city block.

Reading books became my new thing. I read a lot of books…like two per week. I joined book clubs. It played a big part in taking my mind somewhere else. I wanted to read about what motivated other people. I wanted to have more general knowledge. When I hit the three-year mark on my cancer journey, that’s when I started reading autobiographies of people who were in similar situations. The autobiography of Arthur Ash. Magic Johnson. Elizabeth Glaser. They all had AIDS, a fatal disease at that time. So I would read to get an understanding of their experience. Arthur Ash talks about hitting the life expectancy his doctors gave him, and how that felt. So that helped me cope. One woman at my book club even said something like, “You could go back to school with your GI Bill and major in literature! Read, get free books, all that good stuff!”

"It all came down to one final drug…and it was really close to my timeline"

I hit my three-year mark, and then in August of 1998, MD Anderson got approval to start a phase 1 clinical trial on STI571 (Gleevec), led by Dr. Druker who was based in Oregon. I was the second person to receive this treatment at the clinical trial site at MD Anderson. There were three sites of about 20 patients each. The drug was working, but we didn’t know for how long. The doctors were basically gauging things in real time, as there was no predicting what would happen. They just didn’t understand the drug well enough yet.

I ended up having amazing results with STI571, and the doctors said I’d probably have a pretty normal lifespan. In January 1999, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (LLS), who helped fund the trial contacted me and asked if I wanted to be something called a “patient hero.” They said some people would run a marathon in my honor and raise money for cancer research.

As I mentioned earlier, running has always been a huge part of my life. I had been the captain of my high school cross country and track teams. When I was 15 years old, I qualified for the Boston Marathon with 20 minutes to spare, despite having never ran more than eight miles in practice. Everyone was saying that my marathon time was one of the best times in the country for a sophomore. The only problem was, you had to be 18 years-old to run in the Boston Marathon. I was too young, so I never ran another marathon, and stayed with the shorter high school middle distances.

I had always wanted to do another marathon since that solo high school effort, but had never got back around to it. So when I was asked about being a patient hero, I pretty much knew my body and what was required to run a marathon, so I said, “I’ll do the patient hero marathon myself and raise the money also.” And that’s exactly what I did. MD Anderson received special approval to raise my dose to 250 mg daily, so my blood essentially returned to normal range. So much for my first oncologist’s advice, “Don’t run any marathons.”

And then in January 2000, I took my book club friend’s advice and went back to school and received a BA in English Literature, an M.Ed. in Secondary English, and a license to teach. I still had military benefits, so they paid for it. The book club really motivated me.

“Before all of this, I was living every day with the next thing in mind”

In the military, you’re always kind of going for that next promotion. I was a Major, then almost Lieutenant Colonel. So I was moving up the ranks. But when I got the news of CML, all of that stuff just went out the window. My next promotion was the last thing on my mind. Since that day, time really seemed to start slowing down. I started to value it more. And that feeling stayed with me for a long time, even after I started on the drug. I felt like I could just experience things in slow motion. Just appreciate reading a book or whatever it was. Even though I was busy, I still appreciated time. I was very present. I was given three years to live, but I thought “Well, three years is a pretty long time!” Because I could have been given 1 year. That would have been more intense.

It did take me a while - maybe 10-15 years after I retired - to really integrate into the newness of being a “civilian.” Because when you’re in the military, it feels like 99% of your life. And then you think the civilian world is 1% of the actual world. But they say “Once you’re a soldier you’re a soldier for life.” So I still feel like a soldier, even after all these years.

“To me, it feels like a miracle”

The first miracle I was looking for was the bone marrow transplant. The drive organizers used to give out these cups that said “You’re going to find your miracle.” It was a risky procedure, given that back then you had a 50/50 chance of surviving the transplant, since transplants were still pretty new. I knew people who had a transplant and died. And many others opted to not pursue a transplant. “Better three years than six months,” they reasoned. But my daughter was only five years old, so I was willing to take the gamble.

I didn’t end up finding that miracle, but I found a different one that I didn’t see coming, thanks to clinical trials. Sometimes you’ve been in the throes of it for so long, that you almost forget to take a step back and reflect on it. But this journey has made me look at life in a way where I value things more. Because I was so close to not making it. A friend of mine, who was a child when he was diagnosed, was saying how if we had been diagnosed two or three years earlier, we wouldn’t be here. It’s just such a huge feeling of relief.

“This story is bigger than what we thought it was”

I started Gleevec in August 1998. At the time, it was not popular or well-known. No one was talking about it. But eventually as it showed more and more promise, people caught on. And people who started the drug many months after me were given credit for being the longest living survivors on Gleevec. I had been saying through the years that I was the longest living, but was ignored and dismissed. Other patients were featured in best-selling books and spoke on national and international panels about it. I was written out of history and became a hidden figure.

It was not until social media came along, sixteen years later in 2014, - when there were no gatekeepers - that my story really started to get picked up. I had built up my social media audience to half a million followers from some other things, like recruiting marrow donors over the internet, and interacting with the cancer community. So I posted some of my medical records, videos, newspaper clippings, etc. People actually got mad when I said I was the longest living and my medical records proved it. There was a lot of denial, even from some of the popular patient advocates & national organizations. It was kind of funny because I had never really seen another black patient in the very early part of the clinical trial, yet here I was, a black man - someone who wasn’t ‘supposed to be’ in clinical trials - and I had entered the trial before them and lived the longest. I was actually the first Black patient that I saw featured for CML that wasn’t a well-known celebrity.

My doctors changed a few times at MD Anderson. When I was asked to share my journey by MD Anderson and gave them my medical record number for my records they maintained, they said, “This story is bigger than what we thought it was.” And that’s when it kind of blew up. That’s when I started getting credit for being the longest living.

“Progress has been slow. Only 5% of clinical trial participants are black”

When we talk about progress in terms of awareness of and access to clinical trials for black people, there are two key barriers to address: 1) the fact that many people aren’t offered clinical trials to begin with (and therefore don’t even know it’s an option when they’re making a decision about their treatment) and 2) there’s a history of experimentation on the black body.

The travel cost has also been a big discriminator. Back in the early years of my treatment, I traveled back and forth for treatment every three months. I even lived in Houston for three months. That was just part of the protocol at the time. But a lot of people couldn’t afford that or take time off from work or from caring for their families and pets. But now because of the pandemic, people have realized that you don’t always have to travel for clinical trials. There’s a lot you can do right in your own city in terms of testing and things. I’m seeing a shift now where they’re trying to bring clinical trials closer to the patient. Because even for some people who live in a big city, if they are poor, trying to take the bus can still be a hassle.

Progress has been slow, but I’m seeing a ton of education about clinical trials to help people overcome fear. And that’s why I think my story is important, because you see a person who’s been on a clinical trial and you see the long-term survivor. If a clinical trial only buys someone another few months, people will ask if that’s worth it. But when they see someone who has survived five or ten more years, it becomes promising. It’s hard to dispute it because it worked. So patient stories are important, because patients going through it trust patients who have been through it (like I trusted the man who introduced me to clinical trials).

“We were on the front lines”

Today, getting a CML diagnosis is much different than it was back then. When I reminisce with other patients who were on the same trial as me, we know that we were on the front lines of a clinical trial that is now a standard treatment, and is saving the lives of patients who in the past were incurable."

Learn more about Mel’s story:

PBS Stories from the Stage: Living with Cancer (Aired: 06/05/23)

The Mel Mann Story: From Terminal Cancer to 28 Year Survivor

MD Anderson Video on how a Clinical Trial and Gleevec saved Mel Mann's life

“I was commissioned into the Army when I graduated from college. My plan was to do 20 years, retire at 42, get another job, and then eventually retire from that one. But none of that materialized. The whole trajectory for my life changed. I was diagnosed with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) in 1995 and given three years to live. Yet 28 years later, I’m still here.

“I didn’t want to be a blurry memory to my daughter”

When I received my diagnosis, it was scary. Because it’s moments like that where, for the first time, it really sets in that you might not be here forever. My wife Cecelia and I were in our mid 30s when I was diagnosed. Not being here for my family is where most of my worry and emotion stemmed from. She was shocked when I told her.

We told my daughter Patrice as much as we could given her age. She was five-years-old at the time, but she actually understood a lot of it. When the doctors told me I had three years to live, I thought of her, and was immediately counting how old she’d been when I reached the end of those three years. And then thought back to when I was that age, and remembered my grandmother died when I was in third grade…the exact same age. We have old pictures of my grandmother, but my memory of her is blurry. I knew I didn’t want to be a blurry memory to my daughter.

When I shared the news with my Mom, it was really hard on her. Because of course kids aren’t supposed to go before their parents. And my brother had passed in ‘91, just a few years prior. He was 15 years older than me. I was the baby of the family. I knew that losing another child would be really difficult. But ultimately, I feel blessed that I could tell her in person…that we weren’t distanced in the middle of a pandemic.

Ultimately, the emotional aspect of things turned out to be a good thing. Without those feelings, I’m not sure I would have fought as hard as I did. It’s what kept driving me.

“This was a real-life introduction to health disparities and the social determinants of health”

When I was diagnosed, I really hadn’t been sick my entire life. My medical record was like 1 page. I had great insurance through the military, but I didn’t really understand the healthcare system. I had poor health literacy. It wasn’t until my diagnosis - particularly when I was told that my only option was to find a bone marrow donor - where I started to understand the system better. My doctor told me that in 1994 (just one year prior) 2,000 African Americans needed bone marrow transplants, yet only 20 of them found life-saving donors. This was a real life introduction to health disparities and the social determinants of health.

We held bone marrow drives on my base in Detroit, at the mall, in churches, and in other bases around the country. Our community really rallied around the cause. Officers and other co-workers helped organize the bone marrow drives and their spouses did refreshments. My military team managed drives in other parts of the world. Kids would come by our house to cut the grass. People even told me they’d have a pity party if I wanted one. I had such tremendous support from family, friends, the military, and the Church.

We worked really hard during those drives. It wasn’t easy. But I realized that so much of what I learned in the military was still relevant to these new challenges I was facing. I was able to use my military background to create recruitment strategies for the marrow registry, and figure out what would motivate someone to join. It also prepared me to face rejection a lot. When you’re asking people to do stuff, only a few of them will say yes. But you need to keep in mind that if you get 2/10, that’s excellent. So that mindset helped me with that. Somebody else who hadn’t already learned that life lesson may have felt discouraged by that number.

Education was a really important piece for me. Because if you don’t educate someone before they give a blood sample (or a cheek swab in more recent years), you could find out they are a match, only for them to end up not wanting to go through with donating stem cells or bone marrow. As a patient, it’s a really bad feeling when someone backs out right when you feel so close to being saved. And it happened frequently. Kids and teenagers would find matches, but the donors wouldn’t go through with it. So they died. I of course didn’t want that to happen, which is why I would really educate my friends. I would tell them, "If you’re going to join the registry, then you have to go through with it if you’re a match for someone. Don’t sign up if you’re not ready to see it through."

“It gave my life meaning”

Over time, the odds of me finding a match weren’t promising. And there was still no approved drug available yet. But I still felt like this advocacy work had become my calling…that this is what I was supposed to be doing. It gave me another reason for living. It gave my life meaning. So I felt good about that. I’ll never forget receiving a phone call from a marrow donor representative in Detroit. I had just moved to Atlanta 6 months prior when she called. She said, “Remember that church drive we had with the two little girls, where only two people showed up? Well we just set a world record. 5,000 people came out for a little girl with leukemia.” This news felt really great. It felt like a movement, filled with people who each played their own important part of its success. I was just so glad to be part of it. The military was my entire life for so long…my advocacy work has sort of replaced that. And the number of donors at the drives only kept growing.

“16 months into my diagnosis, I learned about a clinical trial option for the first time”

When I was first diagnosed, I went to five different doctors. They all said the same thing…that I needed to find a bone marrow donor (which was abysmal, given that only around 1% of black folks who needed transplants found a donor). So I thought this was my fate.

But then, 16 months into my diagnosis, I learned about a clinical trial option for the first time. The guy who told me about it was at one of the bone marrow drives. He looked really in shape. I could tell he was an athlete. And it turns out he was an avid cyclist. He told me about his hairy cell leukemia diagnosis, and that he was near death before joining a clinical trial. He explained it all so vividly. I could visualize his experience, and even just looking at him in front of me, it gave me hope.

So I decided to travel to one of the clinical trial sites at MD Anderson in Houston. When I met my doctor, I discovered he was the first doctor to use interferon for CML, which was the first-line therapy at the time. He was one of the best in the world and was leading a trial for the current drug they were investigating for CML, and had also discovered a gradual improvement in efficacy for a different treatment. He carefully reviewed my records and said, “We still have time. I’m going to increase your dose of interferon and put you on clinical trial after clinical trial.”

This marked the first time I was informed of and asked to participate in a clinical trial. I realized then that I had experienced a 16-month delay of having an option to receive state-of-the-art medical treatment. It is often stated that some patients, especially some African Americans, are afraid they will be taken advantage of in clinical trials because of the past legacy of unethical experiments, including the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study. However, the reason may stem more from health inequities and lack of opportunities to participate in clinical trials for minorities. I saw clinical trials as a chance to get “tomorrow’s medicine, today.”

The doctors I had back in Atlanta were more traditional than the ones in Houston. They’d question why I even felt the need to go to MD Anderson. I didn’t know much about medicine, but I figured you never know. I knew what my other options were, and they weren’t good. So I thought perhaps maybe one of these other experimental drugs would work…or at least just keep me around longer. Eventually I decided to leave the military’s health system in Atlanta and completely took the civilian route in Houston, since those doctors, at the time, were more progressive. There have been some positive changes in the military’s health system since those years.

“It became a cycle of highs and lows”

The clinical trials I joined were hopeful, but it sort of became this cycle of highs and lows. The treatment would work for a period of time and then 30 days later it wouldn’t. So I’d feel happy and then disappointed, on repeat.

As I approached my three-year mark, the interferon as well as other experimental drugs had stopped working. I would wake up in the morning feeling like I never went to sleep. I was a lifelong runner. I remember looking out the hotel window at the Rotary House International at MD Anderson, thinking about going for a jog, but realizing that I couldn't jog even one city block.

Reading books became my new thing. I read a lot of books…like two per week. I joined book clubs. It played a big part in taking my mind somewhere else. I wanted to read about what motivated other people. I wanted to have more general knowledge. When I hit the three-year mark on my cancer journey, that’s when I started reading autobiographies of people who were in similar situations. The autobiography of Arthur Ash. Magic Johnson. Elizabeth Glaser. They all had AIDS, a fatal disease at that time. So I would read to get an understanding of their experience. Arthur Ash talks about hitting the life expectancy his doctors gave him, and how that felt. So that helped me cope. One woman at my book club even said something like, “You could go back to school with your GI Bill and major in literature! Read, get free books, all that good stuff!”

"It all came down to one final drug…and it was really close to my timeline"

I hit my three-year mark, and then in August of 1998, MD Anderson got approval to start a phase 1 clinical trial on STI571 (Gleevec), led by Dr. Druker who was based in Oregon. I was the second person to receive this treatment at the clinical trial site at MD Anderson. There were three sites of about 20 patients each. The drug was working, but we didn’t know for how long. The doctors were basically gauging things in real time, as there was no predicting what would happen. They just didn’t understand the drug well enough yet.

I ended up having amazing results with STI571, and the doctors said I’d probably have a pretty normal lifespan. In January 1999, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (LLS), who helped fund the trial contacted me and asked if I wanted to be something called a “patient hero.” They said some people would run a marathon in my honor and raise money for cancer research.

As I mentioned earlier, running has always been a huge part of my life. I had been the captain of my high school cross country and track teams. When I was 15 years old, I qualified for the Boston Marathon with 20 minutes to spare, despite having never ran more than eight miles in practice. Everyone was saying that my marathon time was one of the best times in the country for a sophomore. The only problem was, you had to be 18 years-old to run in the Boston Marathon. I was too young, so I never ran another marathon, and stayed with the shorter high school middle distances.

I had always wanted to do another marathon since that solo high school effort, but had never got back around to it. So when I was asked about being a patient hero, I pretty much knew my body and what was required to run a marathon, so I said, “I’ll do the patient hero marathon myself and raise the money also.” And that’s exactly what I did. MD Anderson received special approval to raise my dose to 250 mg daily, so my blood essentially returned to normal range. So much for my first oncologist’s advice, “Don’t run any marathons.”

And then in January 2000, I took my book club friend’s advice and went back to school and received a BA in English Literature, an M.Ed. in Secondary English, and a license to teach. I still had military benefits, so they paid for it. The book club really motivated me.

“Before all of this, I was living every day with the next thing in mind”

In the military, you’re always kind of going for that next promotion. I was a Major, then almost Lieutenant Colonel. So I was moving up the ranks. But when I got the news of CML, all of that stuff just went out the window. My next promotion was the last thing on my mind. Since that day, time really seemed to start slowing down. I started to value it more. And that feeling stayed with me for a long time, even after I started on the drug. I felt like I could just experience things in slow motion. Just appreciate reading a book or whatever it was. Even though I was busy, I still appreciated time. I was very present. I was given three years to live, but I thought “Well, three years is a pretty long time!” Because I could have been given 1 year. That would have been more intense.

It did take me a while - maybe 10-15 years after I retired - to really integrate into the newness of being a “civilian.” Because when you’re in the military, it feels like 99% of your life. And then you think the civilian world is 1% of the actual world. But they say “Once you’re a soldier you’re a soldier for life.” So I still feel like a soldier, even after all these years.

“To me, it feels like a miracle”

The first miracle I was looking for was the bone marrow transplant. The drive organizers used to give out these cups that said “You’re going to find your miracle.” It was a risky procedure, given that back then you had a 50/50 chance of surviving the transplant, since transplants were still pretty new. I knew people who had a transplant and died. And many others opted to not pursue a transplant. “Better three years than six months,” they reasoned. But my daughter was only five years old, so I was willing to take the gamble.

I didn’t end up finding that miracle, but I found a different one that I didn’t see coming, thanks to clinical trials. Sometimes you’ve been in the throes of it for so long, that you almost forget to take a step back and reflect on it. But this journey has made me look at life in a way where I value things more. Because I was so close to not making it. A friend of mine, who was a child when he was diagnosed, was saying how if we had been diagnosed two or three years earlier, we wouldn’t be here. It’s just such a huge feeling of relief.

“This story is bigger than what we thought it was”

I started Gleevec in August 1998. At the time, it was not popular or well-known. No one was talking about it. But eventually as it showed more and more promise, people caught on. And people who started the drug many months after me were given credit for being the longest living survivors on Gleevec. I had been saying through the years that I was the longest living, but was ignored and dismissed. Other patients were featured in best-selling books and spoke on national and international panels about it. I was written out of history and became a hidden figure.

It was not until social media came along, sixteen years later in 2014, - when there were no gatekeepers - that my story really started to get picked up. I had built up my social media audience to half a million followers from some other things, like recruiting marrow donors over the internet, and interacting with the cancer community. So I posted some of my medical records, videos, newspaper clippings, etc. People actually got mad when I said I was the longest living and my medical records proved it. There was a lot of denial, even from some of the popular patient advocates & national organizations. It was kind of funny because I had never really seen another black patient in the very early part of the clinical trial, yet here I was, a black man - someone who wasn’t ‘supposed to be’ in clinical trials - and I had entered the trial before them and lived the longest. I was actually the first Black patient that I saw featured for CML that wasn’t a well-known celebrity.

My doctors changed a few times at MD Anderson. When I was asked to share my journey by MD Anderson and gave them my medical record number for my records they maintained, they said, “This story is bigger than what we thought it was.” And that’s when it kind of blew up. That’s when I started getting credit for being the longest living.

“Progress has been slow. Only 5% of clinical trial participants are black”

When we talk about progress in terms of awareness of and access to clinical trials for black people, there are two key barriers to address: 1) the fact that many people aren’t offered clinical trials to begin with (and therefore don’t even know it’s an option when they’re making a decision about their treatment) and 2) there’s a history of experimentation on the black body.

The travel cost has also been a big discriminator. Back in the early years of my treatment, I traveled back and forth for treatment every three months. I even lived in Houston for three months. That was just part of the protocol at the time. But a lot of people couldn’t afford that or take time off from work or from caring for their families and pets. But now because of the pandemic, people have realized that you don’t always have to travel for clinical trials. There’s a lot you can do right in your own city in terms of testing and things. I’m seeing a shift now where they’re trying to bring clinical trials closer to the patient. Because even for some people who live in a big city, if they are poor, trying to take the bus can still be a hassle.

Progress has been slow, but I’m seeing a ton of education about clinical trials to help people overcome fear. And that’s why I think my story is important, because you see a person who’s been on a clinical trial and you see the long-term survivor. If a clinical trial only buys someone another few months, people will ask if that’s worth it. But when they see someone who has survived five or ten more years, it becomes promising. It’s hard to dispute it because it worked. So patient stories are important, because patients going through it trust patients who have been through it (like I trusted the man who introduced me to clinical trials).

“We were on the front lines”

Today, getting a CML diagnosis is much different than it was back then. When I reminisce with other patients who were on the same trial as me, we know that we were on the front lines of a clinical trial that is now a standard treatment, and is saving the lives of patients who in the past were incurable."

Learn more about Mel’s story:

PBS Stories from the Stage: Living with Cancer (Aired: 06/05/23)

The Mel Mann Story: From Terminal Cancer to 28 Year Survivor

MD Anderson Video on how a Clinical Trial and Gleevec saved Mel Mann's life

“I was commissioned into the Army when I graduated from college. My plan was to do 20 years, retire at 42, get another job, and then eventually retire from that one. But none of that materialized. The whole trajectory for my life changed. I was diagnosed with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) in 1995 and given three years to live. Yet 28 years later, I’m still here.

“I didn’t want to be a blurry memory to my daughter”

When I received my diagnosis, it was scary. Because it’s moments like that where, for the first time, it really sets in that you might not be here forever. My wife Cecelia and I were in our mid 30s when I was diagnosed. Not being here for my family is where most of my worry and emotion stemmed from. She was shocked when I told her.

We told my daughter Patrice as much as we could given her age. She was five-years-old at the time, but she actually understood a lot of it. When the doctors told me I had three years to live, I thought of her, and was immediately counting how old she’d been when I reached the end of those three years. And then thought back to when I was that age, and remembered my grandmother died when I was in third grade…the exact same age. We have old pictures of my grandmother, but my memory of her is blurry. I knew I didn’t want to be a blurry memory to my daughter.

When I shared the news with my Mom, it was really hard on her. Because of course kids aren’t supposed to go before their parents. And my brother had passed in ‘91, just a few years prior. He was 15 years older than me. I was the baby of the family. I knew that losing another child would be really difficult. But ultimately, I feel blessed that I could tell her in person…that we weren’t distanced in the middle of a pandemic.

Ultimately, the emotional aspect of things turned out to be a good thing. Without those feelings, I’m not sure I would have fought as hard as I did. It’s what kept driving me.

“This was a real-life introduction to health disparities and the social determinants of health”

When I was diagnosed, I really hadn’t been sick my entire life. My medical record was like 1 page. I had great insurance through the military, but I didn’t really understand the healthcare system. I had poor health literacy. It wasn’t until my diagnosis - particularly when I was told that my only option was to find a bone marrow donor - where I started to understand the system better. My doctor told me that in 1994 (just one year prior) 2,000 African Americans needed bone marrow transplants, yet only 20 of them found life-saving donors. This was a real life introduction to health disparities and the social determinants of health.

We held bone marrow drives on my base in Detroit, at the mall, in churches, and in other bases around the country. Our community really rallied around the cause. Officers and other co-workers helped organize the bone marrow drives and their spouses did refreshments. My military team managed drives in other parts of the world. Kids would come by our house to cut the grass. People even told me they’d have a pity party if I wanted one. I had such tremendous support from family, friends, the military, and the Church.

We worked really hard during those drives. It wasn’t easy. But I realized that so much of what I learned in the military was still relevant to these new challenges I was facing. I was able to use my military background to create recruitment strategies for the marrow registry, and figure out what would motivate someone to join. It also prepared me to face rejection a lot. When you’re asking people to do stuff, only a few of them will say yes. But you need to keep in mind that if you get 2/10, that’s excellent. So that mindset helped me with that. Somebody else who hadn’t already learned that life lesson may have felt discouraged by that number.

Education was a really important piece for me. Because if you don’t educate someone before they give a blood sample (or a cheek swab in more recent years), you could find out they are a match, only for them to end up not wanting to go through with donating stem cells or bone marrow. As a patient, it’s a really bad feeling when someone backs out right when you feel so close to being saved. And it happened frequently. Kids and teenagers would find matches, but the donors wouldn’t go through with it. So they died. I of course didn’t want that to happen, which is why I would really educate my friends. I would tell them, "If you’re going to join the registry, then you have to go through with it if you’re a match for someone. Don’t sign up if you’re not ready to see it through."

“It gave my life meaning”

Over time, the odds of me finding a match weren’t promising. And there was still no approved drug available yet. But I still felt like this advocacy work had become my calling…that this is what I was supposed to be doing. It gave me another reason for living. It gave my life meaning. So I felt good about that. I’ll never forget receiving a phone call from a marrow donor representative in Detroit. I had just moved to Atlanta 6 months prior when she called. She said, “Remember that church drive we had with the two little girls, where only two people showed up? Well we just set a world record. 5,000 people came out for a little girl with leukemia.” This news felt really great. It felt like a movement, filled with people who each played their own important part of its success. I was just so glad to be part of it. The military was my entire life for so long…my advocacy work has sort of replaced that. And the number of donors at the drives only kept growing.

“16 months into my diagnosis, I learned about a clinical trial option for the first time”

When I was first diagnosed, I went to five different doctors. They all said the same thing…that I needed to find a bone marrow donor (which was abysmal, given that only around 1% of black folks who needed transplants found a donor). So I thought this was my fate.

But then, 16 months into my diagnosis, I learned about a clinical trial option for the first time. The guy who told me about it was at one of the bone marrow drives. He looked really in shape. I could tell he was an athlete. And it turns out he was an avid cyclist. He told me about his hairy cell leukemia diagnosis, and that he was near death before joining a clinical trial. He explained it all so vividly. I could visualize his experience, and even just looking at him in front of me, it gave me hope.

So I decided to travel to one of the clinical trial sites at MD Anderson in Houston. When I met my doctor, I discovered he was the first doctor to use interferon for CML, which was the first-line therapy at the time. He was one of the best in the world and was leading a trial for the current drug they were investigating for CML, and had also discovered a gradual improvement in efficacy for a different treatment. He carefully reviewed my records and said, “We still have time. I’m going to increase your dose of interferon and put you on clinical trial after clinical trial.”

This marked the first time I was informed of and asked to participate in a clinical trial. I realized then that I had experienced a 16-month delay of having an option to receive state-of-the-art medical treatment. It is often stated that some patients, especially some African Americans, are afraid they will be taken advantage of in clinical trials because of the past legacy of unethical experiments, including the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study. However, the reason may stem more from health inequities and lack of opportunities to participate in clinical trials for minorities. I saw clinical trials as a chance to get “tomorrow’s medicine, today.”

The doctors I had back in Atlanta were more traditional than the ones in Houston. They’d question why I even felt the need to go to MD Anderson. I didn’t know much about medicine, but I figured you never know. I knew what my other options were, and they weren’t good. So I thought perhaps maybe one of these other experimental drugs would work…or at least just keep me around longer. Eventually I decided to leave the military’s health system in Atlanta and completely took the civilian route in Houston, since those doctors, at the time, were more progressive. There have been some positive changes in the military’s health system since those years.

“It became a cycle of highs and lows”

The clinical trials I joined were hopeful, but it sort of became this cycle of highs and lows. The treatment would work for a period of time and then 30 days later it wouldn’t. So I’d feel happy and then disappointed, on repeat.

As I approached my three-year mark, the interferon as well as other experimental drugs had stopped working. I would wake up in the morning feeling like I never went to sleep. I was a lifelong runner. I remember looking out the hotel window at the Rotary House International at MD Anderson, thinking about going for a jog, but realizing that I couldn't jog even one city block.

Reading books became my new thing. I read a lot of books…like two per week. I joined book clubs. It played a big part in taking my mind somewhere else. I wanted to read about what motivated other people. I wanted to have more general knowledge. When I hit the three-year mark on my cancer journey, that’s when I started reading autobiographies of people who were in similar situations. The autobiography of Arthur Ash. Magic Johnson. Elizabeth Glaser. They all had AIDS, a fatal disease at that time. So I would read to get an understanding of their experience. Arthur Ash talks about hitting the life expectancy his doctors gave him, and how that felt. So that helped me cope. One woman at my book club even said something like, “You could go back to school with your GI Bill and major in literature! Read, get free books, all that good stuff!”

"It all came down to one final drug…and it was really close to my timeline"

I hit my three-year mark, and then in August of 1998, MD Anderson got approval to start a phase 1 clinical trial on STI571 (Gleevec), led by Dr. Druker who was based in Oregon. I was the second person to receive this treatment at the clinical trial site at MD Anderson. There were three sites of about 20 patients each. The drug was working, but we didn’t know for how long. The doctors were basically gauging things in real time, as there was no predicting what would happen. They just didn’t understand the drug well enough yet.

I ended up having amazing results with STI571, and the doctors said I’d probably have a pretty normal lifespan. In January 1999, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (LLS), who helped fund the trial contacted me and asked if I wanted to be something called a “patient hero.” They said some people would run a marathon in my honor and raise money for cancer research.

As I mentioned earlier, running has always been a huge part of my life. I had been the captain of my high school cross country and track teams. When I was 15 years old, I qualified for the Boston Marathon with 20 minutes to spare, despite having never ran more than eight miles in practice. Everyone was saying that my marathon time was one of the best times in the country for a sophomore. The only problem was, you had to be 18 years-old to run in the Boston Marathon. I was too young, so I never ran another marathon, and stayed with the shorter high school middle distances.

I had always wanted to do another marathon since that solo high school effort, but had never got back around to it. So when I was asked about being a patient hero, I pretty much knew my body and what was required to run a marathon, so I said, “I’ll do the patient hero marathon myself and raise the money also.” And that’s exactly what I did. MD Anderson received special approval to raise my dose to 250 mg daily, so my blood essentially returned to normal range. So much for my first oncologist’s advice, “Don’t run any marathons.”

And then in January 2000, I took my book club friend’s advice and went back to school and received a BA in English Literature, an M.Ed. in Secondary English, and a license to teach. I still had military benefits, so they paid for it. The book club really motivated me.

“Before all of this, I was living every day with the next thing in mind”

In the military, you’re always kind of going for that next promotion. I was a Major, then almost Lieutenant Colonel. So I was moving up the ranks. But when I got the news of CML, all of that stuff just went out the window. My next promotion was the last thing on my mind. Since that day, time really seemed to start slowing down. I started to value it more. And that feeling stayed with me for a long time, even after I started on the drug. I felt like I could just experience things in slow motion. Just appreciate reading a book or whatever it was. Even though I was busy, I still appreciated time. I was very present. I was given three years to live, but I thought “Well, three years is a pretty long time!” Because I could have been given 1 year. That would have been more intense.

It did take me a while - maybe 10-15 years after I retired - to really integrate into the newness of being a “civilian.” Because when you’re in the military, it feels like 99% of your life. And then you think the civilian world is 1% of the actual world. But they say “Once you’re a soldier you’re a soldier for life.” So I still feel like a soldier, even after all these years.

“To me, it feels like a miracle”

The first miracle I was looking for was the bone marrow transplant. The drive organizers used to give out these cups that said “You’re going to find your miracle.” It was a risky procedure, given that back then you had a 50/50 chance of surviving the transplant, since transplants were still pretty new. I knew people who had a transplant and died. And many others opted to not pursue a transplant. “Better three years than six months,” they reasoned. But my daughter was only five years old, so I was willing to take the gamble.

I didn’t end up finding that miracle, but I found a different one that I didn’t see coming, thanks to clinical trials. Sometimes you’ve been in the throes of it for so long, that you almost forget to take a step back and reflect on it. But this journey has made me look at life in a way where I value things more. Because I was so close to not making it. A friend of mine, who was a child when he was diagnosed, was saying how if we had been diagnosed two or three years earlier, we wouldn’t be here. It’s just such a huge feeling of relief.

“This story is bigger than what we thought it was”

I started Gleevec in August 1998. At the time, it was not popular or well-known. No one was talking about it. But eventually as it showed more and more promise, people caught on. And people who started the drug many months after me were given credit for being the longest living survivors on Gleevec. I had been saying through the years that I was the longest living, but was ignored and dismissed. Other patients were featured in best-selling books and spoke on national and international panels about it. I was written out of history and became a hidden figure.

It was not until social media came along, sixteen years later in 2014, - when there were no gatekeepers - that my story really started to get picked up. I had built up my social media audience to half a million followers from some other things, like recruiting marrow donors over the internet, and interacting with the cancer community. So I posted some of my medical records, videos, newspaper clippings, etc. People actually got mad when I said I was the longest living and my medical records proved it. There was a lot of denial, even from some of the popular patient advocates & national organizations. It was kind of funny because I had never really seen another black patient in the very early part of the clinical trial, yet here I was, a black man - someone who wasn’t ‘supposed to be’ in clinical trials - and I had entered the trial before them and lived the longest. I was actually the first Black patient that I saw featured for CML that wasn’t a well-known celebrity.

My doctors changed a few times at MD Anderson. When I was asked to share my journey by MD Anderson and gave them my medical record number for my records they maintained, they said, “This story is bigger than what we thought it was.” And that’s when it kind of blew up. That’s when I started getting credit for being the longest living.

“Progress has been slow. Only 5% of clinical trial participants are black”

When we talk about progress in terms of awareness of and access to clinical trials for black people, there are two key barriers to address: 1) the fact that many people aren’t offered clinical trials to begin with (and therefore don’t even know it’s an option when they’re making a decision about their treatment) and 2) there’s a history of experimentation on the black body.

The travel cost has also been a big discriminator. Back in the early years of my treatment, I traveled back and forth for treatment every three months. I even lived in Houston for three months. That was just part of the protocol at the time. But a lot of people couldn’t afford that or take time off from work or from caring for their families and pets. But now because of the pandemic, people have realized that you don’t always have to travel for clinical trials. There’s a lot you can do right in your own city in terms of testing and things. I’m seeing a shift now where they’re trying to bring clinical trials closer to the patient. Because even for some people who live in a big city, if they are poor, trying to take the bus can still be a hassle.

Progress has been slow, but I’m seeing a ton of education about clinical trials to help people overcome fear. And that’s why I think my story is important, because you see a person who’s been on a clinical trial and you see the long-term survivor. If a clinical trial only buys someone another few months, people will ask if that’s worth it. But when they see someone who has survived five or ten more years, it becomes promising. It’s hard to dispute it because it worked. So patient stories are important, because patients going through it trust patients who have been through it (like I trusted the man who introduced me to clinical trials).

“We were on the front lines”

Today, getting a CML diagnosis is much different than it was back then. When I reminisce with other patients who were on the same trial as me, we know that we were on the front lines of a clinical trial that is now a standard treatment, and is saving the lives of patients who in the past were incurable."

Learn more about Mel’s story:

PBS Stories from the Stage: Living with Cancer (Aired: 06/05/23)

The Mel Mann Story: From Terminal Cancer to 28 Year Survivor

MD Anderson Video on how a Clinical Trial and Gleevec saved Mel Mann's life

"I tell caregivers not to forget to take care of themselves and maintain their health. They need to schedule free time. Don’t wait until the patient is well, to do self-care."

Representation Matters

Increasing diversity in clinical trials builds trust, promotes health equity, and leads to more effective treatments and better outcomes (NEJM). But there is much work to be done - and barriers to break - to improve awareness and access for all people.

Do you know someone who is a member of a marginalized community who has participated in a clinical trial? If so, we’d love to meet them and share their story. We hope to represent the many faces of clinical trials through this project, and inspire others by shining a light on their experience.

They can contact us here.