“He is the Dad I wish I could give everyone on the planet.”

“I never understood why people said they wanted to die when their loved one died. I would think to myself, “No, you have to keep living!” But I get it now. I would have crawled into the coffin with him. I never wanted him to go.”

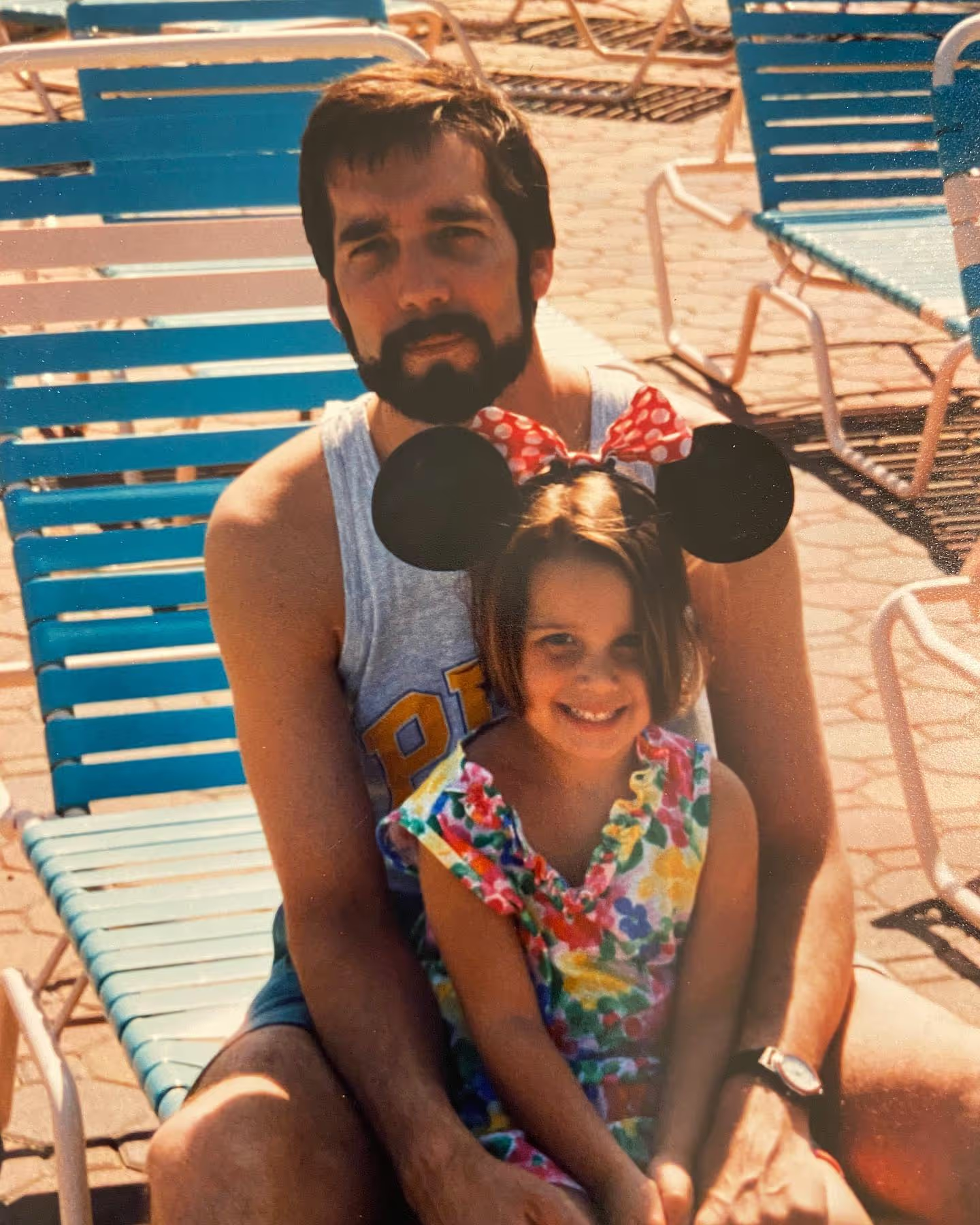

I grew up in a small town of just under 1,500 people in Mars, Pennsylvania. We were a normal family with lots of love. I was always happy being an average kid. My parents raised us under one core principle: “Don’t be an asshole.” It was never “Be extraordinary, be fantastic, be the perfect student or be the perfect athlete.” My Dad would say things like, “Be you. Be a good human. Be a good person. Success and the things you’re passionate about will follow that.” He is the Dad I wish I could give everybody on the planet. My Dad is our North Star.

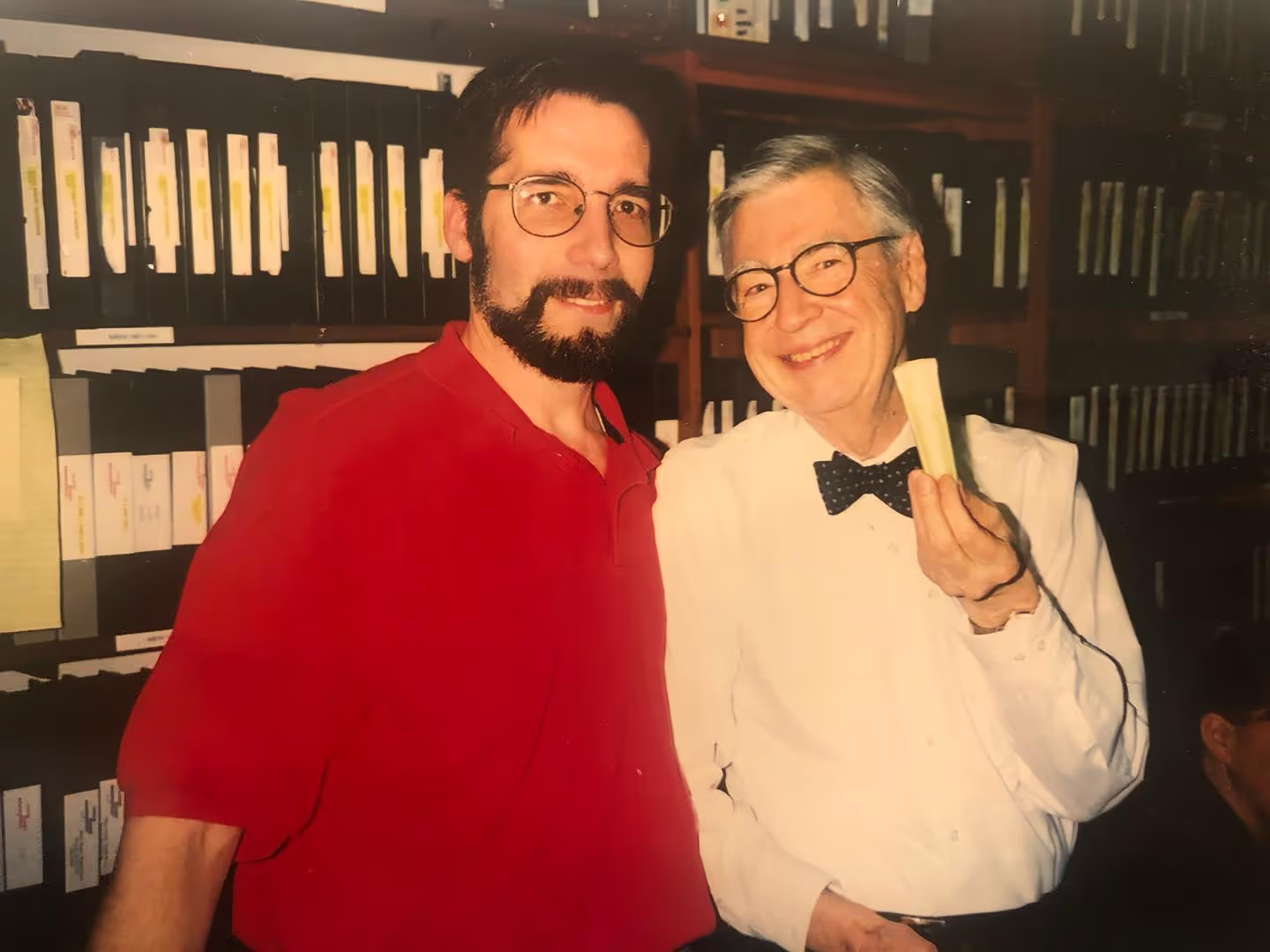

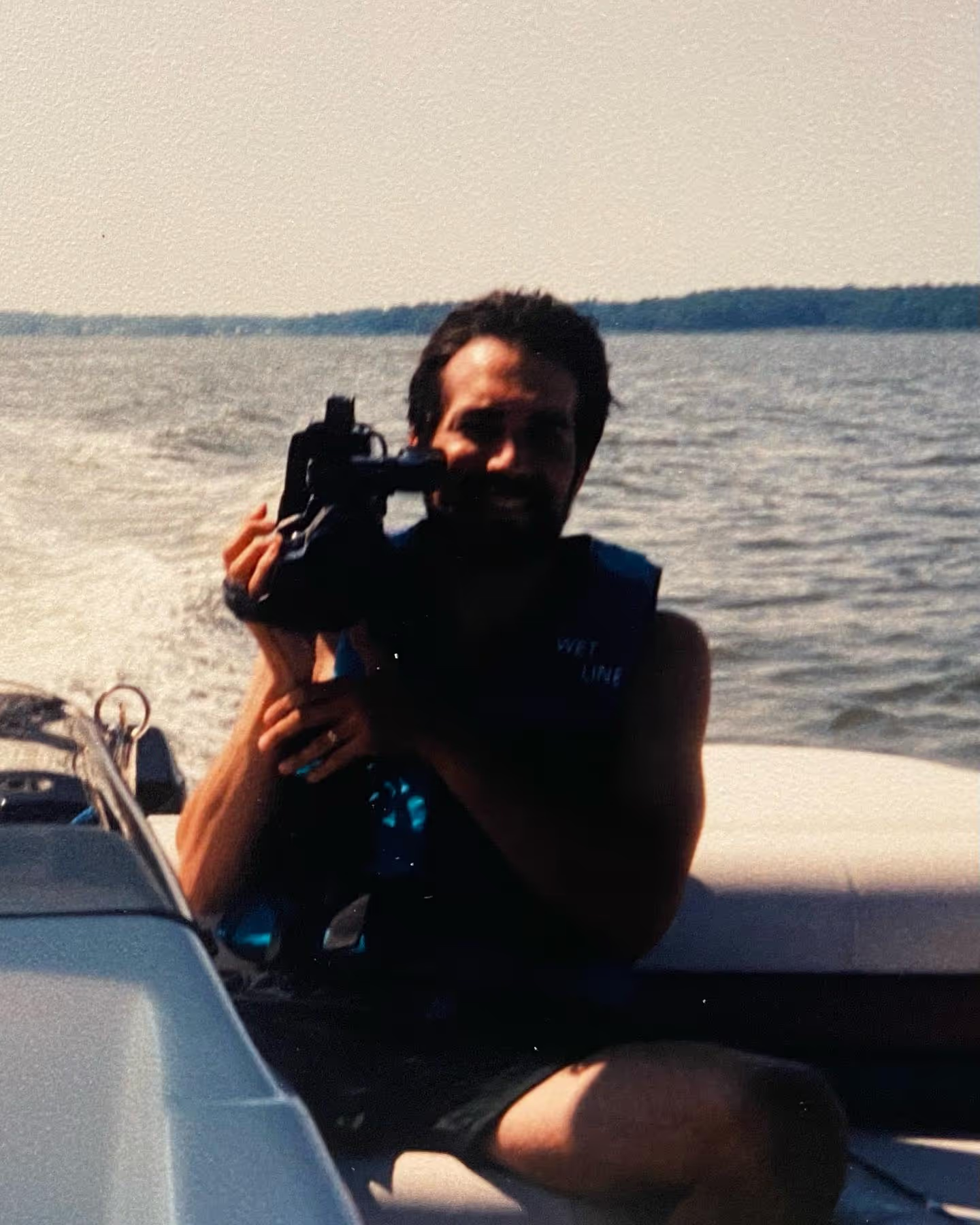

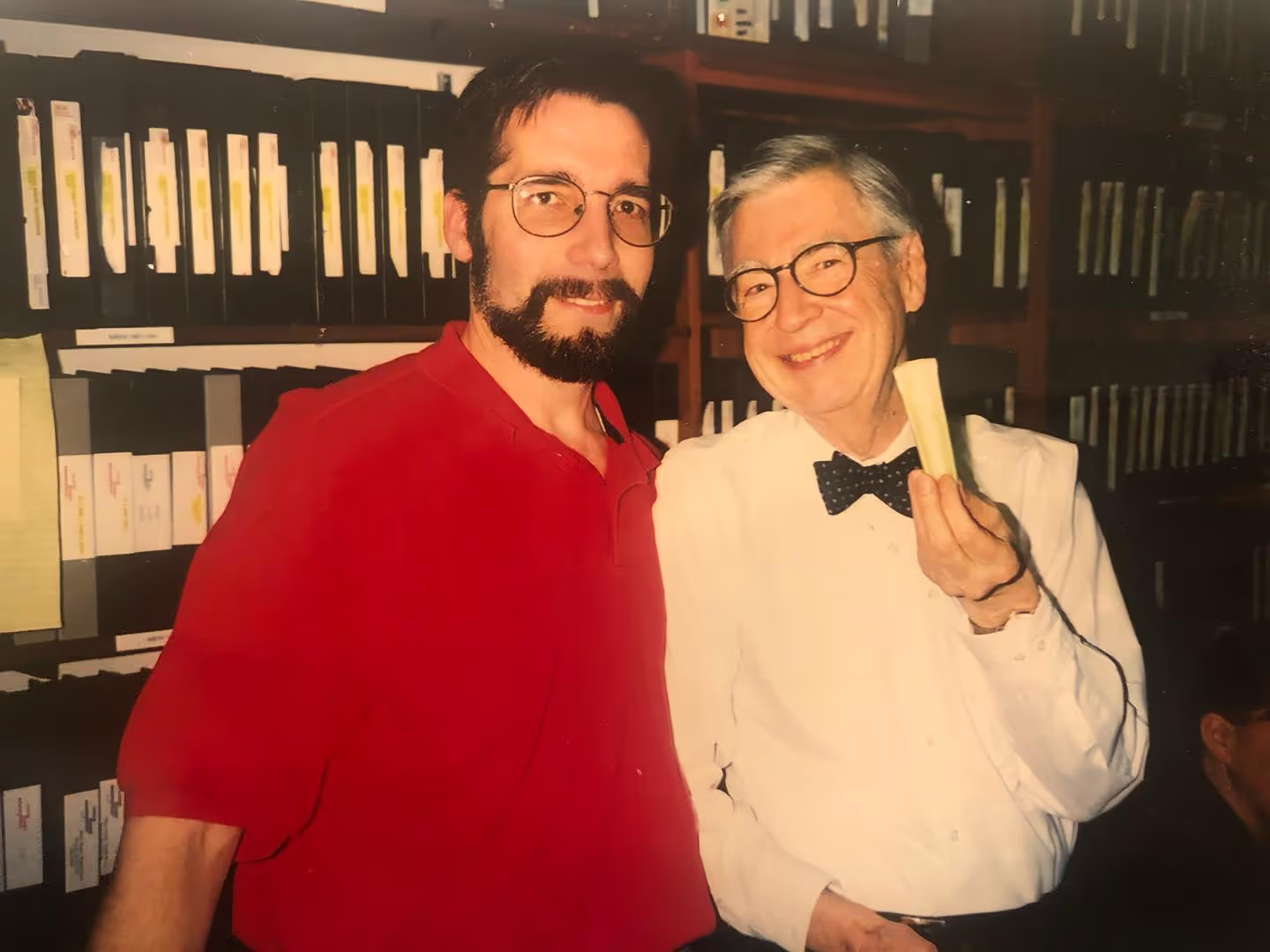

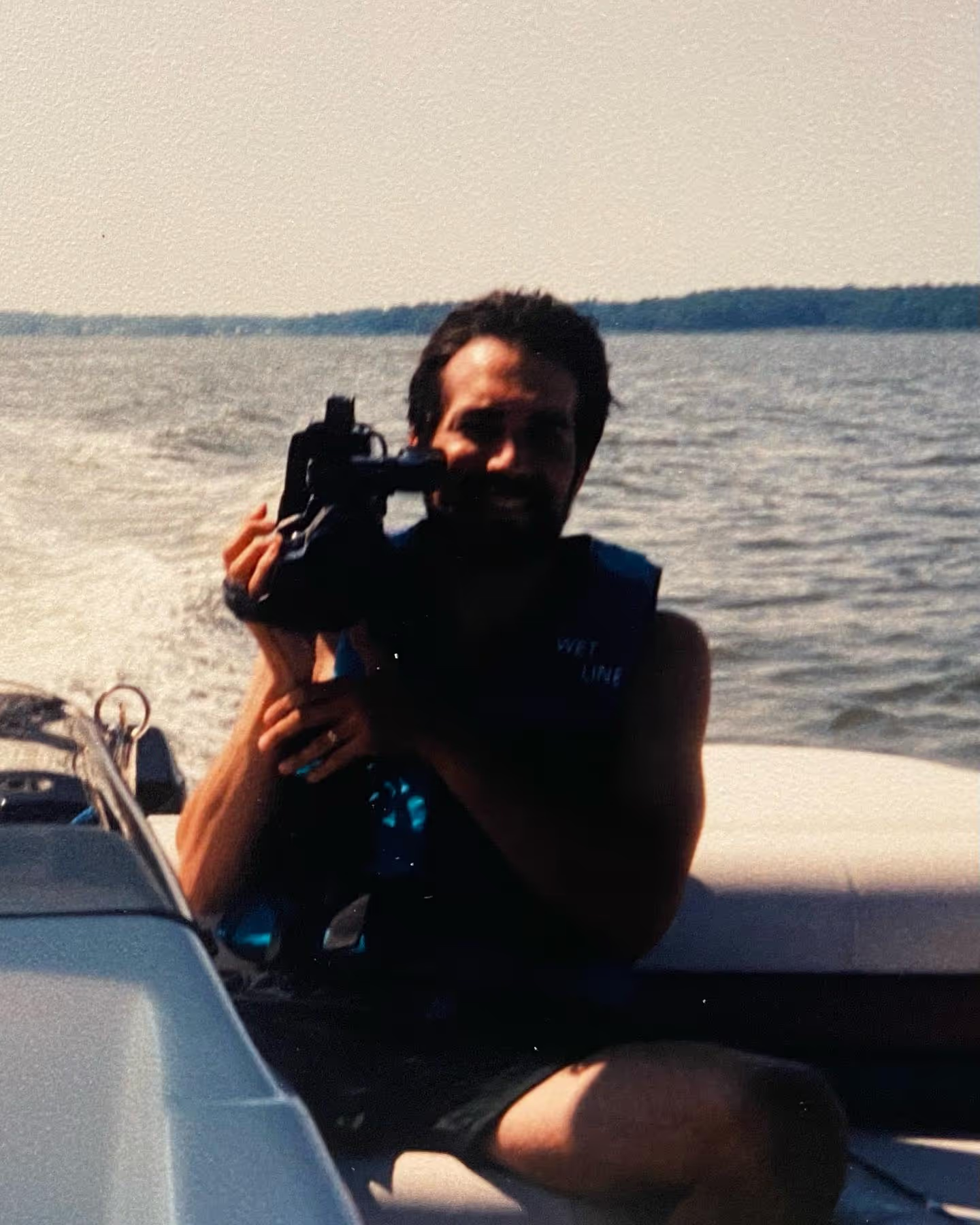

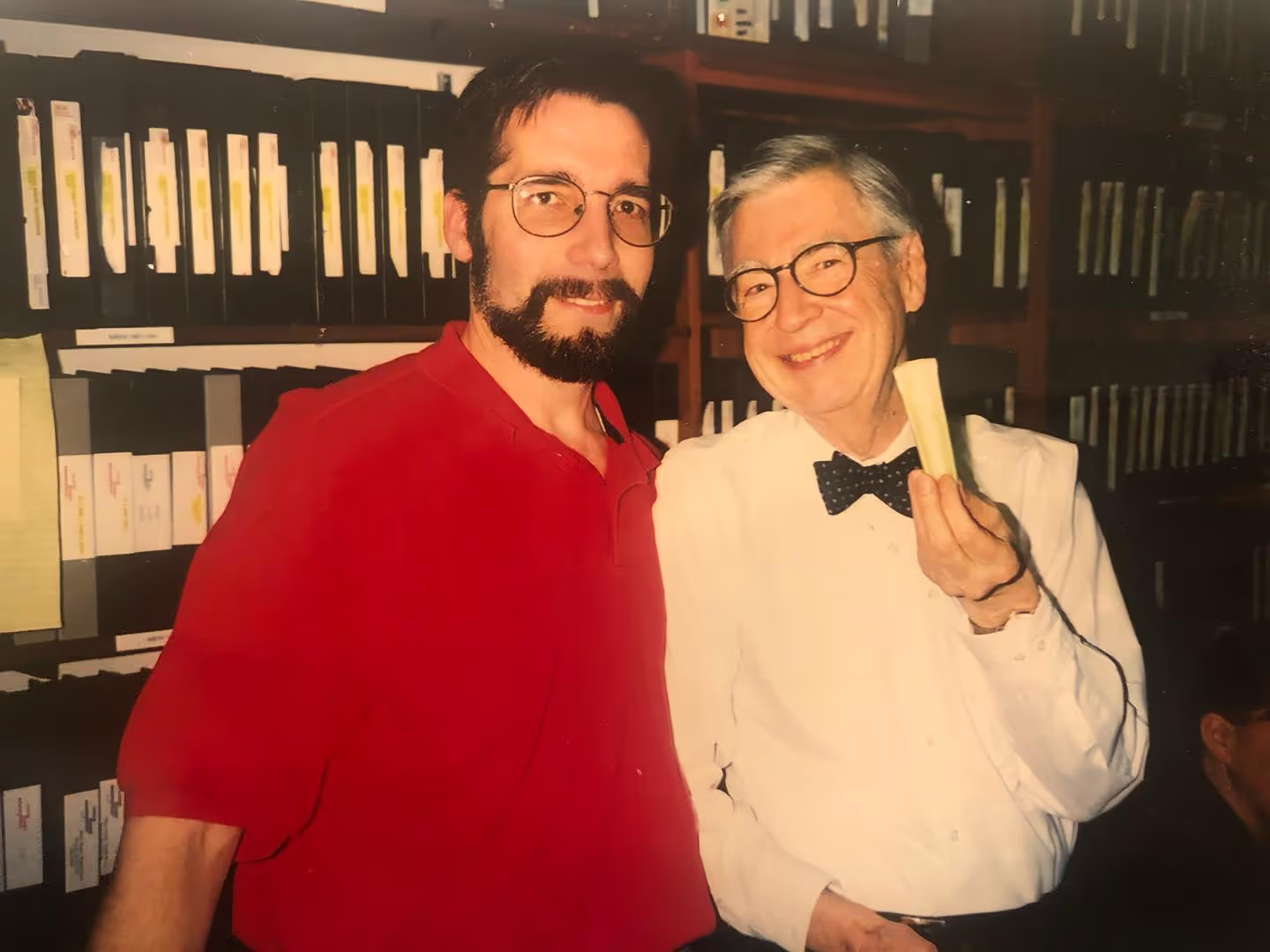

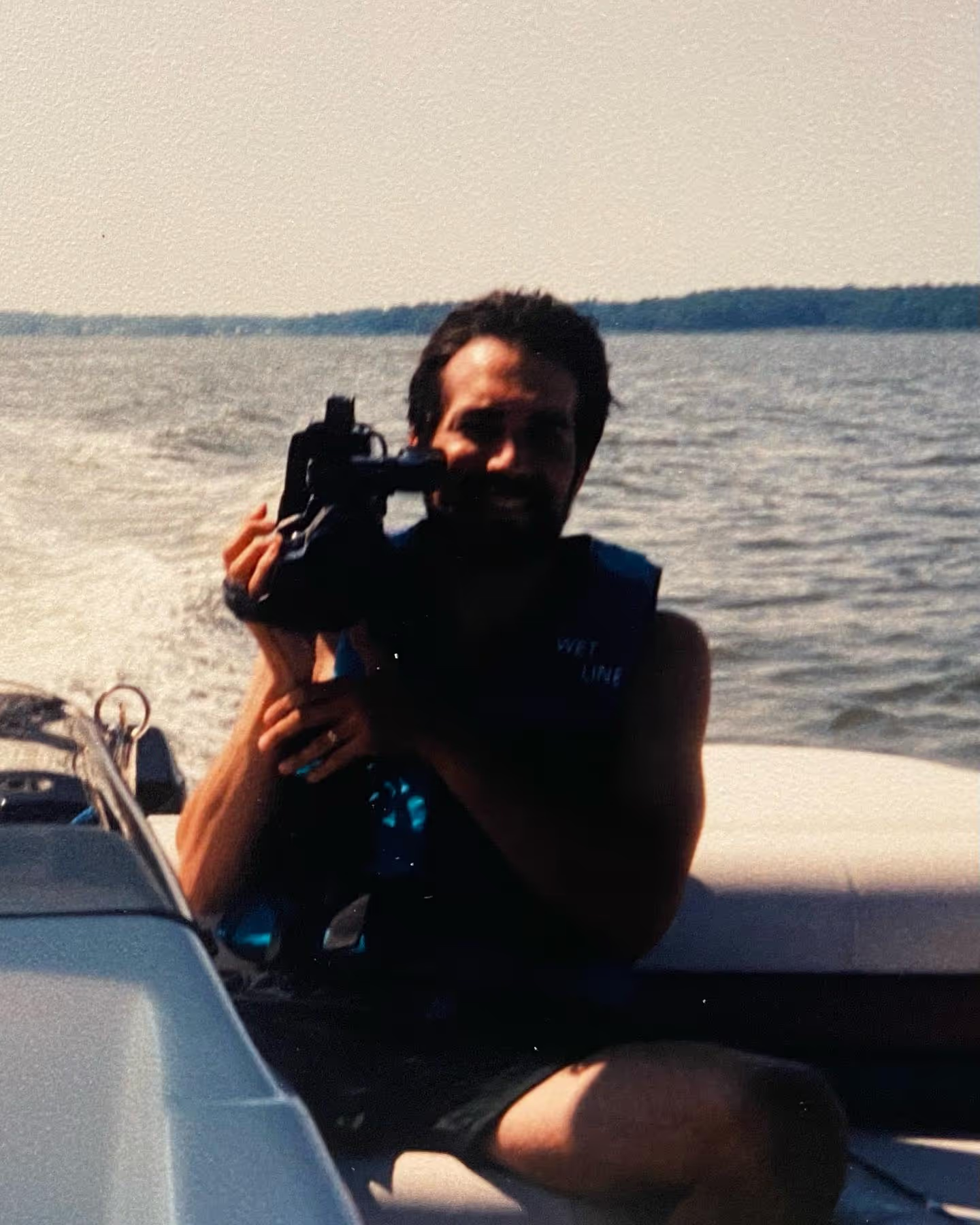

He worked multiple jobs to support our family, including documentary work as a Premier Editor for WQED Pittsburgh (PBS). He created stories for a living. How cool is that? His legacy is woven through the city of Pittsburgh. He worked on Mister Rogers Neighborhood, and we got to meet Fred, which was the coolest thing to experience as a kid. He was also Rick Sebak’s longtime collaborator on many memorable Pittsburgh History programs, and humbly won five Emmy Awards along the way. I think my Dad’s work really shaped him into the incredible father he was, and still is. I talk about him in present tense because he is still all of these things. He is still the incredible person that he was for my whole life, even though he’s no longer earthside.

In 2009, two days before I started college, we got a phone call we didn’t expect.

We learned our Dad had stage 4 head and neck cancer, and it was aggressive. He had a lump in his neck for a couple of years and doctors would say, “It’s probably nothing. We’ll keep an eye on it.” I could talk all day about whether or not I’m still upset that they might have found it sooner. But you really have to advocate for yourself in our healthcare system, and my Dad was never one to make a fuss about himself or his own health.

It all happened so fast. He moved me into college and then almost immediately started chemotherapy. My first year of college was spent going back and forth, helping as much as I could. I’m the second oldest of five kids (the oldest daughter). At the time, I had 3 younger siblings at home, ranging from 5-years-old to 15-years-old. My mom worked so hard to be both a parent and a caretaker. It was too much for one person to bear. She devoted her life to being his caretaker and I’m so grateful that she did.

When he was going through chemo, he didn’t come out of his bedroom.

We barely saw him. He didn’t want anyone to know how sick he was. It took a huge toll on all of us. He was my best friend and he didn’t want us to be part of it. He pushed my Mom away too. But she never complained. She put her life on hold for 11 years, but never once said things like, “This is so unfair for me” or “I shouldn’t have to do this.” It was a dedication unlike anything I’d seen before. Now that I’m married, I understand that kind of partnership.

After he got through that initial round of chemo, they shifted to radiation and were targeting smaller spots of cancer in his neck. He also endured several surgeries during this time to remove spots in his neck. He was never fully in remission, but the cancer would always abate enough that they could stop treatment for a period. We lived in three-month sprints in between PET scans: three months of fun, and then the PET scan, which would tell us if he needed a different treatment or if he’d get another three months without it. It was a “watch and wait” situation for a long time, with pockets of peace and happiness. We’d travel and live as much as we could, because once he recovered from treatment side effects, you’d never know that man was sick!

I moved to Arizona in 2016. It was the hardest decision I ever made because of the distance.

My dad wanted me to go so badly. He said, “You have to do this. This is going to change your life. It’s a good career opportunity. You can’t keep caring for me and your mom. You have to go. You have to get out of this town and live.” And so I went. I had two nickels in my bank account but still came back home often. I was always figuring out how to be at every Christmas and every Thanksgiving, because I never knew when it’d be the last one.

In October 2016, my Dad’s cancer metastasized very deeply into his lungs. They did a massive surgery to remove two-thirds of his left lung. We thought maybe this was the last of it, and that it’d just be a few tiny spots here and there. It was false hope, though. We knew we were trudging down this long road of the inevitable, because the cancer was relentless. But how do you say no to more time? Are you crazy? We would never.

All good things must come to an end, though. During a routine PET scan, in my Dad’s words, “I lit up like a Christmas tree.” If you know anything about PET scans, you know they light up when there’s cancer identified. So that was the point where the doctors said, "There’s nothing left. There are no other approved drugs that we can throw at this. Your only option now is clinical trials."

I had no idea what a clinical trial was. My dad ended up being in multiple.

At first, it felt like he was a lab rat. But he was willing to do anything because it was a chance for him to live longer. I was so deeply uneducated on clinical research at the time, and I just assumed everybody had access to them when traditional treatments stopped working. Now that I’m on the other side of this, I realize how lucky we were to be near a giant health network at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, and that my Dad had incredible health insurance, a supportive job, and an oncologist who was willing to explore clinical trials. We weren’t well off; we were just normal people. But my parents never had to go into medical debt to save his life. And his doctor was so committed to getting my Dad every opportunity to survive. It truly felt like he was ready to die right along with him. We owe him everything.

My Dad went through several trials, each buying us a bit more time. Then, Keytruda hit the market. I remember so vividly his oncologist telling us, “This is it. He's a perfect match for this. This is what we've been waiting for.” The other trials and the chemo were to keep him alive long enough for medicine to advance and get to this point. I remember thinking, “This sounds too good to be true. How can this doctor be so sure?” But I’ve realized that doctors are humans. They’re very smart humans, but they are humans that are just trying to do their best. Unfortunately, there was no improvement for my Dad. The drug did nothing other than make him really sick. That was the last treatment they tried.

It was downhill from there. 2020 came and was horrific in so many ways. They kept looking for options. His oncologist got moved to a new hospital which felt impossible to navigate, and then the pandemic hit. He was trying to get into another trial as he was actively starting to die. Fluid continuously collected in his chest from his lung removal in 2016, and our Mom had to learn how to drain a chest catheter at home so he could breath, due to the pandemic limiting nurses coming into homes.

We had my Dad locked in the house, because COVID would have knocked him out in an instant.

We were really strict with protocols. We had to be. He was so afraid of dying alone. It was horrifying. Along with his stage 4 head and neck cancer, he also suffered from skin cancer and prostate cancer, all in the span of 11 years.

Three months before his death, on a call with his oncologist, my Dad was begging for her to find him another clinical trial. He was skin and bones at this point and nearing hospice care. There was nothing left to do. I said, “Dad, you’re not going to make it. You’re not going to make it through another clinical trial.” But he’d be damned if he didn’t try. He would have moved the sun, moon, and stars to get more time with us.

During the fall of 2020, my boss at the time said, “Go home. Go be with your dad. I don’t care what it takes, go be with him. I’ll handle your work. I’ll handle your clients. I’ll do the thing so you can do what you need to do.” She gave me what no other human could give: the gift of time. I’m indebted to her for this until the day I die.

I temporarily moved home from Idaho. We tried to make him as comfortable as possible as we watched him die.

In December of 2020, three days before his death, we noticed he was sleeping much later than normal. It was odd. When we checked on him, we found him in severe respiratory distress. He was on hospice at the time, so we weren’t supposed to call 911. But he told us to call. He didn’t want to die like that. So we called, they got him to the hospital, and we found out he had pneumonia and sepsis. It was a mess. Hospice told me, “You weren’t supposed to call.” I said, “Well, I’m sorry, but I called. Because that’s what my Dad wanted.”

That night when we called 911 and he went to the hospital, only my mom was allowed with him.

The hospital was under strict covid protocols, as it was December 2020. We all waited with bated breath on that first night he was there. The hospital staff said it was “just pneumonia” and if they could clear it, he could maybe go home. We were so stupidly optimistic. My mom’s best friend is a doctor at that hospital. She wasn’t my Dad’s doctor, but she took my mom aside and said, “He is dying and we need to accept that. You need to get the kids to accept that because he’s never coming home.” I was so mad at her. I remember thinking that she didn’t know him like I did. He was going to come back home. Years later, when I look back on the one photo we have of him in the hospital before he died, anyone could have immediately known he was never coming home. In moments like that, though, you’re delusional and will believe anything you want to believe.

He died two days later of complications from pneumonia, exacerbated by the fact that his body was riddled with cancer. So he passed in December 2020, after 11 years fighting. It’s incredible. Without clinical trials, we would’ve had half that time, maybe less. So that’s what clinical trials did for my family. They gave us time. Time is such a precious resource.

He and I always wrote letters. That was our way.

We both have this thing where when we get emotional, you can hear it in our voice, and we both immediately start crying. So we wrote letters. I wrote him one the day before he died, and the last text message I have from him says, “I read your letter. It was beautiful. I love you so much.” The last letter I have from him was from March of 2020, when he knew he was going to die. He was always referencing life in terms of “I’m not done.” He was 65 when he died, so not terribly young, but not old enough by any means. I guess he just wanted to be more than what the end of his life let him be.

I don’t think we really understood his legacy and how much he left behind until he died. He was so humble. His employer posted about his death and there were hundreds of comments from people we’ve never met. It was an outpouring of love for him. He won five Emmy Awards and you’d never have known it. He never bragged about himself. He worked at the same place for 40 years and to see his legacy after he died, it was beautiful. I’ve thought to myself, why don’t we show people this stuff when they’re alive?

We’re convinced he found peace, because my mom believes he lives on as a blue jay. We don’t have blue jays out here in Idaho, so I always say, “Well, he hasn’t visited me yet!” If I ever see one, I guess we’ll know it’s real. Blue jays are known to be angry birds, and he was always a little angry. We knew he wouldn’t come back as a cardinal! I think he just felt so robbed because even though he survived cancer for 11 years, his life in many ways stopped at 54. I don’t know how you continue on, knowing you have cancer inside of you that’s trying to kill you. So even though he got some extra time, he wanted more.

He became very closed-off. Stoic and not overly emotional. Cancer made him (and all of us) face the fact that he was not superman. He was not not invincible. He’d be angry and cynical when he was sick, then would act normal once he got through treatment. It was as if he was on vacation when he was sick, and then would return the same person we all loved, throwing a ball in the backyard or driving 12 hours to the beach house. I was old enough to know what he was doing, so it was hard to watch. At the same time, though, I wanted my brothers and sisters to have the Dad they deserved. I’ve always said it was his journey. He deserved to live it the way he felt was best, and that's why he put those walls up - to protect us, and himself, too. He wanted to shield his kids from the ugliness as much as he could. It just really hurts because I feel like he died angry. We’d tell him, “You can let go. It’s okay.” We’d beg him to stop treatment. “You don’t need to put your body through this. We love you so much, but you’re suffering.”

I did so much therapy leading up to his death. I knew it was coming.

I told my therapist, “I’m going to therapy my way through this.” She replied, “My dear, you are not going to therapy your way through this.” And she was right. I tried, but to no one’s surprise, it did not work. I needed to feel. I needed to cry when I needed to cry. If I’m going to be living, then I’m going to be feeling. I grieved out loud to anybody who would listen - and not for sympathy, not for pity, but because it is not normalized. It’s taboo to talk about when it shouldn’t be. Why wouldn’t we celebrate these incredible people that we’ve lost too young? Why wouldn’t we want to talk about them? I’m not going to make myself smaller to make you feel comfortable. I’m grieving something that shaped me so fundamentally that I will never be the same person I was before. I am forever shaped by him. Just by knowing him and being loved by him.

Grief is the most holy thing. It happens to most of us, so it’s universal, but nobody goes through it the same way. It’s so unique. I cope really openly. I don’t ever shy away from talking about him. We’re all going to go through grief at some point in our lives, and if one moment of me sharing my pain can signal to someone that I am a safe space for them to grieve, then that’s what I’m going to do.

Grief sneaks up on you, too. A couple months after he died, I found a Walmart receipt from a purchase of two pairs of sweatpants. My Dad was a jeans-at-home kind of guy. You know those guys? Who never wear anything but jeans around the house? He was so uncomfortable as he neared his death and had lost so much weight. So I decided to get him some sweatpants. When I found the receipt, I had been doing really well. I was back to work, felt on top of things, and really felt like I was getting through it. Then all of a sudden I was sobbing on the floor. That’s what grief is: sobbing on the floor at 7:30 in the morning holding a Walmart receipt, because you’ve been transported back there.

I had a weird dream once, and I'm very convinced it was more than just a dream.

My Dad was in it, and he was at peace. He was healed and whole again. He wasn’t riddled with scars from all of the operations. And he was barefoot, which was so weird, because he was never barefoot. We were all sitting on the couch and he opened the door and we were like, “What?? What are you doing here?" And he said, "I just had to come back and let you know that I'm good."

Wherever he is now, that dream is the only thing that has ever made me believe he’s found peace. He never had it here on Earth. He never said things like, "I'll see you on the other side.” His letters would say how proud he was of me and how I'm going to do great things in my life. It was never, “I’m okay with this. I’m at peace with this.” I firmly believe that him showing up in my dreams is his way of telling me, "I'm good now. I know I wasn’t ready for this, but it's great here. You’ll find out some day.”

He still shows up in my dreams every now and then, but only in the background. And that makes sense. He always worked in the background, making magic behind the scenes as a documentary editor. He never wanted the credit (though it was always given because he was so wonderful). He loved sharing the voices of people who felt voiceless. He loved to bridge together depth and light-heartedness, good and evil, and just take something from the camera and make so much more out of it.

I’m proud to share some of the same traits with him. I work really hard to do the right thing and I don't want recognition. I just want to be in the background, making magic happen like he did. I don't want anyone to know that I was involved. I think he drives me to be that way. I don’t know what drove him, though. I wish I had asked. There are so many things that have come up that I wish I had asked. That’s really my only regret. I don’t regret moving or doing what I had to do all those years. But to anyone who's losing someone, ask them everything you could ever think of. And then ask more!

My professional life is now centered around driving access for patients to clinical research.

As I shared earlier, I knew nothing about clinical trials before my dad was in one, and thought that everyone had equal access and opportunity to participate in them. I now work for the Decentralized Trials and Research Alliance (DTRA), an organization focused on increasing access for patients to clinical research through innovative methods, including decentralized options. The FDA defines a decentralized clinical trial as, “A clinical trial where some or all of a clinical trial’s activities occur at locations other than a traditional clinical trial site. These alternate locations can include the participant’s home, a local health care facility, or a nearby laboratory.”

I grew up in a small town, but we were only 30 minutes away from a huge metropolitan city. It was a privilege that we had access to the health system there. This isn’t the case for many folks. Some will say decentralized methods are too much effort or “We only did that because of the pandemic.” There are many more reasons beyond the pandemic! We need to get access to trials for people who aren’t living in predominantly white, affluent communities with big hospital networks.

Everyone deserves a chance to try something that could extend their life. If we can move past the business side of things and get back to the human side of it, we could save more people’s lives. Yes, it takes a lot of work. But we’re doing it: we’re creating the resources, we’re getting all of the smart people together, we’re trying to better educate communities about clinical trials as an option, and we’re going to figure out how to do this. I believe that knowing you have privilege and doing something about it are two very different things.

This experience has taught me that I am so much more capable than I think I am.

I can do really hard things. I can live a good life while still honoring him. I don't have to die just because he did. I can continue to live and have joy. I can live this really great life and still be devastated that he is not here. Two things can be true at once. I trust that time doesn't heal all, but it does make things a whole hell of a lot easier. It does make things possible.”

https://www.devlinfuneralhome.com/obituaries/kevin-p-conrad/

“I never understood why people said they wanted to die when their loved one died. I would think to myself, “No, you have to keep living!” But I get it now. I would have crawled into the coffin with him. I never wanted him to go.”

I grew up in a small town of just under 1,500 people in Mars, Pennsylvania. We were a normal family with lots of love. I was always happy being an average kid. My parents raised us under one core principle: “Don’t be an asshole.” It was never “Be extraordinary, be fantastic, be the perfect student or be the perfect athlete.” My Dad would say things like, “Be you. Be a good human. Be a good person. Success and the things you’re passionate about will follow that.” He is the Dad I wish I could give everybody on the planet. My Dad is our North Star.

He worked multiple jobs to support our family, including documentary work as a Premier Editor for WQED Pittsburgh (PBS). He created stories for a living. How cool is that? His legacy is woven through the city of Pittsburgh. He worked on Mister Rogers Neighborhood, and we got to meet Fred, which was the coolest thing to experience as a kid. He was also Rick Sebak’s longtime collaborator on many memorable Pittsburgh History programs, and humbly won five Emmy Awards along the way. I think my Dad’s work really shaped him into the incredible father he was, and still is. I talk about him in present tense because he is still all of these things. He is still the incredible person that he was for my whole life, even though he’s no longer earthside.

In 2009, two days before I started college, we got a phone call we didn’t expect.

We learned our Dad had stage 4 head and neck cancer, and it was aggressive. He had a lump in his neck for a couple of years and doctors would say, “It’s probably nothing. We’ll keep an eye on it.” I could talk all day about whether or not I’m still upset that they might have found it sooner. But you really have to advocate for yourself in our healthcare system, and my Dad was never one to make a fuss about himself or his own health.

It all happened so fast. He moved me into college and then almost immediately started chemotherapy. My first year of college was spent going back and forth, helping as much as I could. I’m the second oldest of five kids (the oldest daughter). At the time, I had 3 younger siblings at home, ranging from 5-years-old to 15-years-old. My mom worked so hard to be both a parent and a caretaker. It was too much for one person to bear. She devoted her life to being his caretaker and I’m so grateful that she did.

When he was going through chemo, he didn’t come out of his bedroom.

We barely saw him. He didn’t want anyone to know how sick he was. It took a huge toll on all of us. He was my best friend and he didn’t want us to be part of it. He pushed my Mom away too. But she never complained. She put her life on hold for 11 years, but never once said things like, “This is so unfair for me” or “I shouldn’t have to do this.” It was a dedication unlike anything I’d seen before. Now that I’m married, I understand that kind of partnership.

After he got through that initial round of chemo, they shifted to radiation and were targeting smaller spots of cancer in his neck. He also endured several surgeries during this time to remove spots in his neck. He was never fully in remission, but the cancer would always abate enough that they could stop treatment for a period. We lived in three-month sprints in between PET scans: three months of fun, and then the PET scan, which would tell us if he needed a different treatment or if he’d get another three months without it. It was a “watch and wait” situation for a long time, with pockets of peace and happiness. We’d travel and live as much as we could, because once he recovered from treatment side effects, you’d never know that man was sick!

I moved to Arizona in 2016. It was the hardest decision I ever made because of the distance.

My dad wanted me to go so badly. He said, “You have to do this. This is going to change your life. It’s a good career opportunity. You can’t keep caring for me and your mom. You have to go. You have to get out of this town and live.” And so I went. I had two nickels in my bank account but still came back home often. I was always figuring out how to be at every Christmas and every Thanksgiving, because I never knew when it’d be the last one.

In October 2016, my Dad’s cancer metastasized very deeply into his lungs. They did a massive surgery to remove two-thirds of his left lung. We thought maybe this was the last of it, and that it’d just be a few tiny spots here and there. It was false hope, though. We knew we were trudging down this long road of the inevitable, because the cancer was relentless. But how do you say no to more time? Are you crazy? We would never.

All good things must come to an end, though. During a routine PET scan, in my Dad’s words, “I lit up like a Christmas tree.” If you know anything about PET scans, you know they light up when there’s cancer identified. So that was the point where the doctors said, "There’s nothing left. There are no other approved drugs that we can throw at this. Your only option now is clinical trials."

I had no idea what a clinical trial was. My dad ended up being in multiple.

At first, it felt like he was a lab rat. But he was willing to do anything because it was a chance for him to live longer. I was so deeply uneducated on clinical research at the time, and I just assumed everybody had access to them when traditional treatments stopped working. Now that I’m on the other side of this, I realize how lucky we were to be near a giant health network at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, and that my Dad had incredible health insurance, a supportive job, and an oncologist who was willing to explore clinical trials. We weren’t well off; we were just normal people. But my parents never had to go into medical debt to save his life. And his doctor was so committed to getting my Dad every opportunity to survive. It truly felt like he was ready to die right along with him. We owe him everything.

My Dad went through several trials, each buying us a bit more time. Then, Keytruda hit the market. I remember so vividly his oncologist telling us, “This is it. He's a perfect match for this. This is what we've been waiting for.” The other trials and the chemo were to keep him alive long enough for medicine to advance and get to this point. I remember thinking, “This sounds too good to be true. How can this doctor be so sure?” But I’ve realized that doctors are humans. They’re very smart humans, but they are humans that are just trying to do their best. Unfortunately, there was no improvement for my Dad. The drug did nothing other than make him really sick. That was the last treatment they tried.

It was downhill from there. 2020 came and was horrific in so many ways. They kept looking for options. His oncologist got moved to a new hospital which felt impossible to navigate, and then the pandemic hit. He was trying to get into another trial as he was actively starting to die. Fluid continuously collected in his chest from his lung removal in 2016, and our Mom had to learn how to drain a chest catheter at home so he could breath, due to the pandemic limiting nurses coming into homes.

We had my Dad locked in the house, because COVID would have knocked him out in an instant.

We were really strict with protocols. We had to be. He was so afraid of dying alone. It was horrifying. Along with his stage 4 head and neck cancer, he also suffered from skin cancer and prostate cancer, all in the span of 11 years.

Three months before his death, on a call with his oncologist, my Dad was begging for her to find him another clinical trial. He was skin and bones at this point and nearing hospice care. There was nothing left to do. I said, “Dad, you’re not going to make it. You’re not going to make it through another clinical trial.” But he’d be damned if he didn’t try. He would have moved the sun, moon, and stars to get more time with us.

During the fall of 2020, my boss at the time said, “Go home. Go be with your dad. I don’t care what it takes, go be with him. I’ll handle your work. I’ll handle your clients. I’ll do the thing so you can do what you need to do.” She gave me what no other human could give: the gift of time. I’m indebted to her for this until the day I die.

I temporarily moved home from Idaho. We tried to make him as comfortable as possible as we watched him die.

In December of 2020, three days before his death, we noticed he was sleeping much later than normal. It was odd. When we checked on him, we found him in severe respiratory distress. He was on hospice at the time, so we weren’t supposed to call 911. But he told us to call. He didn’t want to die like that. So we called, they got him to the hospital, and we found out he had pneumonia and sepsis. It was a mess. Hospice told me, “You weren’t supposed to call.” I said, “Well, I’m sorry, but I called. Because that’s what my Dad wanted.”

That night when we called 911 and he went to the hospital, only my mom was allowed with him.

The hospital was under strict covid protocols, as it was December 2020. We all waited with bated breath on that first night he was there. The hospital staff said it was “just pneumonia” and if they could clear it, he could maybe go home. We were so stupidly optimistic. My mom’s best friend is a doctor at that hospital. She wasn’t my Dad’s doctor, but she took my mom aside and said, “He is dying and we need to accept that. You need to get the kids to accept that because he’s never coming home.” I was so mad at her. I remember thinking that she didn’t know him like I did. He was going to come back home. Years later, when I look back on the one photo we have of him in the hospital before he died, anyone could have immediately known he was never coming home. In moments like that, though, you’re delusional and will believe anything you want to believe.

He died two days later of complications from pneumonia, exacerbated by the fact that his body was riddled with cancer. So he passed in December 2020, after 11 years fighting. It’s incredible. Without clinical trials, we would’ve had half that time, maybe less. So that’s what clinical trials did for my family. They gave us time. Time is such a precious resource.

He and I always wrote letters. That was our way.

We both have this thing where when we get emotional, you can hear it in our voice, and we both immediately start crying. So we wrote letters. I wrote him one the day before he died, and the last text message I have from him says, “I read your letter. It was beautiful. I love you so much.” The last letter I have from him was from March of 2020, when he knew he was going to die. He was always referencing life in terms of “I’m not done.” He was 65 when he died, so not terribly young, but not old enough by any means. I guess he just wanted to be more than what the end of his life let him be.

I don’t think we really understood his legacy and how much he left behind until he died. He was so humble. His employer posted about his death and there were hundreds of comments from people we’ve never met. It was an outpouring of love for him. He won five Emmy Awards and you’d never have known it. He never bragged about himself. He worked at the same place for 40 years and to see his legacy after he died, it was beautiful. I’ve thought to myself, why don’t we show people this stuff when they’re alive?

We’re convinced he found peace, because my mom believes he lives on as a blue jay. We don’t have blue jays out here in Idaho, so I always say, “Well, he hasn’t visited me yet!” If I ever see one, I guess we’ll know it’s real. Blue jays are known to be angry birds, and he was always a little angry. We knew he wouldn’t come back as a cardinal! I think he just felt so robbed because even though he survived cancer for 11 years, his life in many ways stopped at 54. I don’t know how you continue on, knowing you have cancer inside of you that’s trying to kill you. So even though he got some extra time, he wanted more.

He became very closed-off. Stoic and not overly emotional. Cancer made him (and all of us) face the fact that he was not superman. He was not not invincible. He’d be angry and cynical when he was sick, then would act normal once he got through treatment. It was as if he was on vacation when he was sick, and then would return the same person we all loved, throwing a ball in the backyard or driving 12 hours to the beach house. I was old enough to know what he was doing, so it was hard to watch. At the same time, though, I wanted my brothers and sisters to have the Dad they deserved. I’ve always said it was his journey. He deserved to live it the way he felt was best, and that's why he put those walls up - to protect us, and himself, too. He wanted to shield his kids from the ugliness as much as he could. It just really hurts because I feel like he died angry. We’d tell him, “You can let go. It’s okay.” We’d beg him to stop treatment. “You don’t need to put your body through this. We love you so much, but you’re suffering.”

I did so much therapy leading up to his death. I knew it was coming.

I told my therapist, “I’m going to therapy my way through this.” She replied, “My dear, you are not going to therapy your way through this.” And she was right. I tried, but to no one’s surprise, it did not work. I needed to feel. I needed to cry when I needed to cry. If I’m going to be living, then I’m going to be feeling. I grieved out loud to anybody who would listen - and not for sympathy, not for pity, but because it is not normalized. It’s taboo to talk about when it shouldn’t be. Why wouldn’t we celebrate these incredible people that we’ve lost too young? Why wouldn’t we want to talk about them? I’m not going to make myself smaller to make you feel comfortable. I’m grieving something that shaped me so fundamentally that I will never be the same person I was before. I am forever shaped by him. Just by knowing him and being loved by him.

Grief is the most holy thing. It happens to most of us, so it’s universal, but nobody goes through it the same way. It’s so unique. I cope really openly. I don’t ever shy away from talking about him. We’re all going to go through grief at some point in our lives, and if one moment of me sharing my pain can signal to someone that I am a safe space for them to grieve, then that’s what I’m going to do.

Grief sneaks up on you, too. A couple months after he died, I found a Walmart receipt from a purchase of two pairs of sweatpants. My Dad was a jeans-at-home kind of guy. You know those guys? Who never wear anything but jeans around the house? He was so uncomfortable as he neared his death and had lost so much weight. So I decided to get him some sweatpants. When I found the receipt, I had been doing really well. I was back to work, felt on top of things, and really felt like I was getting through it. Then all of a sudden I was sobbing on the floor. That’s what grief is: sobbing on the floor at 7:30 in the morning holding a Walmart receipt, because you’ve been transported back there.

I had a weird dream once, and I'm very convinced it was more than just a dream.

My Dad was in it, and he was at peace. He was healed and whole again. He wasn’t riddled with scars from all of the operations. And he was barefoot, which was so weird, because he was never barefoot. We were all sitting on the couch and he opened the door and we were like, “What?? What are you doing here?" And he said, "I just had to come back and let you know that I'm good."

Wherever he is now, that dream is the only thing that has ever made me believe he’s found peace. He never had it here on Earth. He never said things like, "I'll see you on the other side.” His letters would say how proud he was of me and how I'm going to do great things in my life. It was never, “I’m okay with this. I’m at peace with this.” I firmly believe that him showing up in my dreams is his way of telling me, "I'm good now. I know I wasn’t ready for this, but it's great here. You’ll find out some day.”

He still shows up in my dreams every now and then, but only in the background. And that makes sense. He always worked in the background, making magic behind the scenes as a documentary editor. He never wanted the credit (though it was always given because he was so wonderful). He loved sharing the voices of people who felt voiceless. He loved to bridge together depth and light-heartedness, good and evil, and just take something from the camera and make so much more out of it.

I’m proud to share some of the same traits with him. I work really hard to do the right thing and I don't want recognition. I just want to be in the background, making magic happen like he did. I don't want anyone to know that I was involved. I think he drives me to be that way. I don’t know what drove him, though. I wish I had asked. There are so many things that have come up that I wish I had asked. That’s really my only regret. I don’t regret moving or doing what I had to do all those years. But to anyone who's losing someone, ask them everything you could ever think of. And then ask more!

My professional life is now centered around driving access for patients to clinical research.

As I shared earlier, I knew nothing about clinical trials before my dad was in one, and thought that everyone had equal access and opportunity to participate in them. I now work for the Decentralized Trials and Research Alliance (DTRA), an organization focused on increasing access for patients to clinical research through innovative methods, including decentralized options. The FDA defines a decentralized clinical trial as, “A clinical trial where some or all of a clinical trial’s activities occur at locations other than a traditional clinical trial site. These alternate locations can include the participant’s home, a local health care facility, or a nearby laboratory.”

I grew up in a small town, but we were only 30 minutes away from a huge metropolitan city. It was a privilege that we had access to the health system there. This isn’t the case for many folks. Some will say decentralized methods are too much effort or “We only did that because of the pandemic.” There are many more reasons beyond the pandemic! We need to get access to trials for people who aren’t living in predominantly white, affluent communities with big hospital networks.

Everyone deserves a chance to try something that could extend their life. If we can move past the business side of things and get back to the human side of it, we could save more people’s lives. Yes, it takes a lot of work. But we’re doing it: we’re creating the resources, we’re getting all of the smart people together, we’re trying to better educate communities about clinical trials as an option, and we’re going to figure out how to do this. I believe that knowing you have privilege and doing something about it are two very different things.

This experience has taught me that I am so much more capable than I think I am.

I can do really hard things. I can live a good life while still honoring him. I don't have to die just because he did. I can continue to live and have joy. I can live this really great life and still be devastated that he is not here. Two things can be true at once. I trust that time doesn't heal all, but it does make things a whole hell of a lot easier. It does make things possible.”

https://www.devlinfuneralhome.com/obituaries/kevin-p-conrad/

“I never understood why people said they wanted to die when their loved one died. I would think to myself, “No, you have to keep living!” But I get it now. I would have crawled into the coffin with him. I never wanted him to go.”

I grew up in a small town of just under 1,500 people in Mars, Pennsylvania. We were a normal family with lots of love. I was always happy being an average kid. My parents raised us under one core principle: “Don’t be an asshole.” It was never “Be extraordinary, be fantastic, be the perfect student or be the perfect athlete.” My Dad would say things like, “Be you. Be a good human. Be a good person. Success and the things you’re passionate about will follow that.” He is the Dad I wish I could give everybody on the planet. My Dad is our North Star.

He worked multiple jobs to support our family, including documentary work as a Premier Editor for WQED Pittsburgh (PBS). He created stories for a living. How cool is that? His legacy is woven through the city of Pittsburgh. He worked on Mister Rogers Neighborhood, and we got to meet Fred, which was the coolest thing to experience as a kid. He was also Rick Sebak’s longtime collaborator on many memorable Pittsburgh History programs, and humbly won five Emmy Awards along the way. I think my Dad’s work really shaped him into the incredible father he was, and still is. I talk about him in present tense because he is still all of these things. He is still the incredible person that he was for my whole life, even though he’s no longer earthside.

In 2009, two days before I started college, we got a phone call we didn’t expect.

We learned our Dad had stage 4 head and neck cancer, and it was aggressive. He had a lump in his neck for a couple of years and doctors would say, “It’s probably nothing. We’ll keep an eye on it.” I could talk all day about whether or not I’m still upset that they might have found it sooner. But you really have to advocate for yourself in our healthcare system, and my Dad was never one to make a fuss about himself or his own health.

It all happened so fast. He moved me into college and then almost immediately started chemotherapy. My first year of college was spent going back and forth, helping as much as I could. I’m the second oldest of five kids (the oldest daughter). At the time, I had 3 younger siblings at home, ranging from 5-years-old to 15-years-old. My mom worked so hard to be both a parent and a caretaker. It was too much for one person to bear. She devoted her life to being his caretaker and I’m so grateful that she did.

When he was going through chemo, he didn’t come out of his bedroom.

We barely saw him. He didn’t want anyone to know how sick he was. It took a huge toll on all of us. He was my best friend and he didn’t want us to be part of it. He pushed my Mom away too. But she never complained. She put her life on hold for 11 years, but never once said things like, “This is so unfair for me” or “I shouldn’t have to do this.” It was a dedication unlike anything I’d seen before. Now that I’m married, I understand that kind of partnership.

After he got through that initial round of chemo, they shifted to radiation and were targeting smaller spots of cancer in his neck. He also endured several surgeries during this time to remove spots in his neck. He was never fully in remission, but the cancer would always abate enough that they could stop treatment for a period. We lived in three-month sprints in between PET scans: three months of fun, and then the PET scan, which would tell us if he needed a different treatment or if he’d get another three months without it. It was a “watch and wait” situation for a long time, with pockets of peace and happiness. We’d travel and live as much as we could, because once he recovered from treatment side effects, you’d never know that man was sick!

I moved to Arizona in 2016. It was the hardest decision I ever made because of the distance.

My dad wanted me to go so badly. He said, “You have to do this. This is going to change your life. It’s a good career opportunity. You can’t keep caring for me and your mom. You have to go. You have to get out of this town and live.” And so I went. I had two nickels in my bank account but still came back home often. I was always figuring out how to be at every Christmas and every Thanksgiving, because I never knew when it’d be the last one.

In October 2016, my Dad’s cancer metastasized very deeply into his lungs. They did a massive surgery to remove two-thirds of his left lung. We thought maybe this was the last of it, and that it’d just be a few tiny spots here and there. It was false hope, though. We knew we were trudging down this long road of the inevitable, because the cancer was relentless. But how do you say no to more time? Are you crazy? We would never.

All good things must come to an end, though. During a routine PET scan, in my Dad’s words, “I lit up like a Christmas tree.” If you know anything about PET scans, you know they light up when there’s cancer identified. So that was the point where the doctors said, "There’s nothing left. There are no other approved drugs that we can throw at this. Your only option now is clinical trials."

I had no idea what a clinical trial was. My dad ended up being in multiple.

At first, it felt like he was a lab rat. But he was willing to do anything because it was a chance for him to live longer. I was so deeply uneducated on clinical research at the time, and I just assumed everybody had access to them when traditional treatments stopped working. Now that I’m on the other side of this, I realize how lucky we were to be near a giant health network at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, and that my Dad had incredible health insurance, a supportive job, and an oncologist who was willing to explore clinical trials. We weren’t well off; we were just normal people. But my parents never had to go into medical debt to save his life. And his doctor was so committed to getting my Dad every opportunity to survive. It truly felt like he was ready to die right along with him. We owe him everything.

My Dad went through several trials, each buying us a bit more time. Then, Keytruda hit the market. I remember so vividly his oncologist telling us, “This is it. He's a perfect match for this. This is what we've been waiting for.” The other trials and the chemo were to keep him alive long enough for medicine to advance and get to this point. I remember thinking, “This sounds too good to be true. How can this doctor be so sure?” But I’ve realized that doctors are humans. They’re very smart humans, but they are humans that are just trying to do their best. Unfortunately, there was no improvement for my Dad. The drug did nothing other than make him really sick. That was the last treatment they tried.

It was downhill from there. 2020 came and was horrific in so many ways. They kept looking for options. His oncologist got moved to a new hospital which felt impossible to navigate, and then the pandemic hit. He was trying to get into another trial as he was actively starting to die. Fluid continuously collected in his chest from his lung removal in 2016, and our Mom had to learn how to drain a chest catheter at home so he could breath, due to the pandemic limiting nurses coming into homes.

We had my Dad locked in the house, because COVID would have knocked him out in an instant.

We were really strict with protocols. We had to be. He was so afraid of dying alone. It was horrifying. Along with his stage 4 head and neck cancer, he also suffered from skin cancer and prostate cancer, all in the span of 11 years.

Three months before his death, on a call with his oncologist, my Dad was begging for her to find him another clinical trial. He was skin and bones at this point and nearing hospice care. There was nothing left to do. I said, “Dad, you’re not going to make it. You’re not going to make it through another clinical trial.” But he’d be damned if he didn’t try. He would have moved the sun, moon, and stars to get more time with us.

During the fall of 2020, my boss at the time said, “Go home. Go be with your dad. I don’t care what it takes, go be with him. I’ll handle your work. I’ll handle your clients. I’ll do the thing so you can do what you need to do.” She gave me what no other human could give: the gift of time. I’m indebted to her for this until the day I die.

I temporarily moved home from Idaho. We tried to make him as comfortable as possible as we watched him die.

In December of 2020, three days before his death, we noticed he was sleeping much later than normal. It was odd. When we checked on him, we found him in severe respiratory distress. He was on hospice at the time, so we weren’t supposed to call 911. But he told us to call. He didn’t want to die like that. So we called, they got him to the hospital, and we found out he had pneumonia and sepsis. It was a mess. Hospice told me, “You weren’t supposed to call.” I said, “Well, I’m sorry, but I called. Because that’s what my Dad wanted.”

That night when we called 911 and he went to the hospital, only my mom was allowed with him.

The hospital was under strict covid protocols, as it was December 2020. We all waited with bated breath on that first night he was there. The hospital staff said it was “just pneumonia” and if they could clear it, he could maybe go home. We were so stupidly optimistic. My mom’s best friend is a doctor at that hospital. She wasn’t my Dad’s doctor, but she took my mom aside and said, “He is dying and we need to accept that. You need to get the kids to accept that because he’s never coming home.” I was so mad at her. I remember thinking that she didn’t know him like I did. He was going to come back home. Years later, when I look back on the one photo we have of him in the hospital before he died, anyone could have immediately known he was never coming home. In moments like that, though, you’re delusional and will believe anything you want to believe.

He died two days later of complications from pneumonia, exacerbated by the fact that his body was riddled with cancer. So he passed in December 2020, after 11 years fighting. It’s incredible. Without clinical trials, we would’ve had half that time, maybe less. So that’s what clinical trials did for my family. They gave us time. Time is such a precious resource.

He and I always wrote letters. That was our way.

We both have this thing where when we get emotional, you can hear it in our voice, and we both immediately start crying. So we wrote letters. I wrote him one the day before he died, and the last text message I have from him says, “I read your letter. It was beautiful. I love you so much.” The last letter I have from him was from March of 2020, when he knew he was going to die. He was always referencing life in terms of “I’m not done.” He was 65 when he died, so not terribly young, but not old enough by any means. I guess he just wanted to be more than what the end of his life let him be.

I don’t think we really understood his legacy and how much he left behind until he died. He was so humble. His employer posted about his death and there were hundreds of comments from people we’ve never met. It was an outpouring of love for him. He won five Emmy Awards and you’d never have known it. He never bragged about himself. He worked at the same place for 40 years and to see his legacy after he died, it was beautiful. I’ve thought to myself, why don’t we show people this stuff when they’re alive?

We’re convinced he found peace, because my mom believes he lives on as a blue jay. We don’t have blue jays out here in Idaho, so I always say, “Well, he hasn’t visited me yet!” If I ever see one, I guess we’ll know it’s real. Blue jays are known to be angry birds, and he was always a little angry. We knew he wouldn’t come back as a cardinal! I think he just felt so robbed because even though he survived cancer for 11 years, his life in many ways stopped at 54. I don’t know how you continue on, knowing you have cancer inside of you that’s trying to kill you. So even though he got some extra time, he wanted more.

He became very closed-off. Stoic and not overly emotional. Cancer made him (and all of us) face the fact that he was not superman. He was not not invincible. He’d be angry and cynical when he was sick, then would act normal once he got through treatment. It was as if he was on vacation when he was sick, and then would return the same person we all loved, throwing a ball in the backyard or driving 12 hours to the beach house. I was old enough to know what he was doing, so it was hard to watch. At the same time, though, I wanted my brothers and sisters to have the Dad they deserved. I’ve always said it was his journey. He deserved to live it the way he felt was best, and that's why he put those walls up - to protect us, and himself, too. He wanted to shield his kids from the ugliness as much as he could. It just really hurts because I feel like he died angry. We’d tell him, “You can let go. It’s okay.” We’d beg him to stop treatment. “You don’t need to put your body through this. We love you so much, but you’re suffering.”

I did so much therapy leading up to his death. I knew it was coming.

I told my therapist, “I’m going to therapy my way through this.” She replied, “My dear, you are not going to therapy your way through this.” And she was right. I tried, but to no one’s surprise, it did not work. I needed to feel. I needed to cry when I needed to cry. If I’m going to be living, then I’m going to be feeling. I grieved out loud to anybody who would listen - and not for sympathy, not for pity, but because it is not normalized. It’s taboo to talk about when it shouldn’t be. Why wouldn’t we celebrate these incredible people that we’ve lost too young? Why wouldn’t we want to talk about them? I’m not going to make myself smaller to make you feel comfortable. I’m grieving something that shaped me so fundamentally that I will never be the same person I was before. I am forever shaped by him. Just by knowing him and being loved by him.

Grief is the most holy thing. It happens to most of us, so it’s universal, but nobody goes through it the same way. It’s so unique. I cope really openly. I don’t ever shy away from talking about him. We’re all going to go through grief at some point in our lives, and if one moment of me sharing my pain can signal to someone that I am a safe space for them to grieve, then that’s what I’m going to do.

Grief sneaks up on you, too. A couple months after he died, I found a Walmart receipt from a purchase of two pairs of sweatpants. My Dad was a jeans-at-home kind of guy. You know those guys? Who never wear anything but jeans around the house? He was so uncomfortable as he neared his death and had lost so much weight. So I decided to get him some sweatpants. When I found the receipt, I had been doing really well. I was back to work, felt on top of things, and really felt like I was getting through it. Then all of a sudden I was sobbing on the floor. That’s what grief is: sobbing on the floor at 7:30 in the morning holding a Walmart receipt, because you’ve been transported back there.

I had a weird dream once, and I'm very convinced it was more than just a dream.

My Dad was in it, and he was at peace. He was healed and whole again. He wasn’t riddled with scars from all of the operations. And he was barefoot, which was so weird, because he was never barefoot. We were all sitting on the couch and he opened the door and we were like, “What?? What are you doing here?" And he said, "I just had to come back and let you know that I'm good."

Wherever he is now, that dream is the only thing that has ever made me believe he’s found peace. He never had it here on Earth. He never said things like, "I'll see you on the other side.” His letters would say how proud he was of me and how I'm going to do great things in my life. It was never, “I’m okay with this. I’m at peace with this.” I firmly believe that him showing up in my dreams is his way of telling me, "I'm good now. I know I wasn’t ready for this, but it's great here. You’ll find out some day.”

He still shows up in my dreams every now and then, but only in the background. And that makes sense. He always worked in the background, making magic behind the scenes as a documentary editor. He never wanted the credit (though it was always given because he was so wonderful). He loved sharing the voices of people who felt voiceless. He loved to bridge together depth and light-heartedness, good and evil, and just take something from the camera and make so much more out of it.

I’m proud to share some of the same traits with him. I work really hard to do the right thing and I don't want recognition. I just want to be in the background, making magic happen like he did. I don't want anyone to know that I was involved. I think he drives me to be that way. I don’t know what drove him, though. I wish I had asked. There are so many things that have come up that I wish I had asked. That’s really my only regret. I don’t regret moving or doing what I had to do all those years. But to anyone who's losing someone, ask them everything you could ever think of. And then ask more!

My professional life is now centered around driving access for patients to clinical research.

As I shared earlier, I knew nothing about clinical trials before my dad was in one, and thought that everyone had equal access and opportunity to participate in them. I now work for the Decentralized Trials and Research Alliance (DTRA), an organization focused on increasing access for patients to clinical research through innovative methods, including decentralized options. The FDA defines a decentralized clinical trial as, “A clinical trial where some or all of a clinical trial’s activities occur at locations other than a traditional clinical trial site. These alternate locations can include the participant’s home, a local health care facility, or a nearby laboratory.”

I grew up in a small town, but we were only 30 minutes away from a huge metropolitan city. It was a privilege that we had access to the health system there. This isn’t the case for many folks. Some will say decentralized methods are too much effort or “We only did that because of the pandemic.” There are many more reasons beyond the pandemic! We need to get access to trials for people who aren’t living in predominantly white, affluent communities with big hospital networks.

Everyone deserves a chance to try something that could extend their life. If we can move past the business side of things and get back to the human side of it, we could save more people’s lives. Yes, it takes a lot of work. But we’re doing it: we’re creating the resources, we’re getting all of the smart people together, we’re trying to better educate communities about clinical trials as an option, and we’re going to figure out how to do this. I believe that knowing you have privilege and doing something about it are two very different things.

This experience has taught me that I am so much more capable than I think I am.

I can do really hard things. I can live a good life while still honoring him. I don't have to die just because he did. I can continue to live and have joy. I can live this really great life and still be devastated that he is not here. Two things can be true at once. I trust that time doesn't heal all, but it does make things a whole hell of a lot easier. It does make things possible.”

https://www.devlinfuneralhome.com/obituaries/kevin-p-conrad/

“I never understood why people said they wanted to die when their loved one died. I would think to myself, “No, you have to keep living!” But I get it now. I would have crawled into the coffin with him. I never wanted him to go.”

I grew up in a small town of just under 1,500 people in Mars, Pennsylvania. We were a normal family with lots of love. I was always happy being an average kid. My parents raised us under one core principle: “Don’t be an asshole.” It was never “Be extraordinary, be fantastic, be the perfect student or be the perfect athlete.” My Dad would say things like, “Be you. Be a good human. Be a good person. Success and the things you’re passionate about will follow that.” He is the Dad I wish I could give everybody on the planet. My Dad is our North Star.

He worked multiple jobs to support our family, including documentary work as a Premier Editor for WQED Pittsburgh (PBS). He created stories for a living. How cool is that? His legacy is woven through the city of Pittsburgh. He worked on Mister Rogers Neighborhood, and we got to meet Fred, which was the coolest thing to experience as a kid. He was also Rick Sebak’s longtime collaborator on many memorable Pittsburgh History programs, and humbly won five Emmy Awards along the way. I think my Dad’s work really shaped him into the incredible father he was, and still is. I talk about him in present tense because he is still all of these things. He is still the incredible person that he was for my whole life, even though he’s no longer earthside.

In 2009, two days before I started college, we got a phone call we didn’t expect.

We learned our Dad had stage 4 head and neck cancer, and it was aggressive. He had a lump in his neck for a couple of years and doctors would say, “It’s probably nothing. We’ll keep an eye on it.” I could talk all day about whether or not I’m still upset that they might have found it sooner. But you really have to advocate for yourself in our healthcare system, and my Dad was never one to make a fuss about himself or his own health.

It all happened so fast. He moved me into college and then almost immediately started chemotherapy. My first year of college was spent going back and forth, helping as much as I could. I’m the second oldest of five kids (the oldest daughter). At the time, I had 3 younger siblings at home, ranging from 5-years-old to 15-years-old. My mom worked so hard to be both a parent and a caretaker. It was too much for one person to bear. She devoted her life to being his caretaker and I’m so grateful that she did.

When he was going through chemo, he didn’t come out of his bedroom.

We barely saw him. He didn’t want anyone to know how sick he was. It took a huge toll on all of us. He was my best friend and he didn’t want us to be part of it. He pushed my Mom away too. But she never complained. She put her life on hold for 11 years, but never once said things like, “This is so unfair for me” or “I shouldn’t have to do this.” It was a dedication unlike anything I’d seen before. Now that I’m married, I understand that kind of partnership.

After he got through that initial round of chemo, they shifted to radiation and were targeting smaller spots of cancer in his neck. He also endured several surgeries during this time to remove spots in his neck. He was never fully in remission, but the cancer would always abate enough that they could stop treatment for a period. We lived in three-month sprints in between PET scans: three months of fun, and then the PET scan, which would tell us if he needed a different treatment or if he’d get another three months without it. It was a “watch and wait” situation for a long time, with pockets of peace and happiness. We’d travel and live as much as we could, because once he recovered from treatment side effects, you’d never know that man was sick!

I moved to Arizona in 2016. It was the hardest decision I ever made because of the distance.

My dad wanted me to go so badly. He said, “You have to do this. This is going to change your life. It’s a good career opportunity. You can’t keep caring for me and your mom. You have to go. You have to get out of this town and live.” And so I went. I had two nickels in my bank account but still came back home often. I was always figuring out how to be at every Christmas and every Thanksgiving, because I never knew when it’d be the last one.

In October 2016, my Dad’s cancer metastasized very deeply into his lungs. They did a massive surgery to remove two-thirds of his left lung. We thought maybe this was the last of it, and that it’d just be a few tiny spots here and there. It was false hope, though. We knew we were trudging down this long road of the inevitable, because the cancer was relentless. But how do you say no to more time? Are you crazy? We would never.

All good things must come to an end, though. During a routine PET scan, in my Dad’s words, “I lit up like a Christmas tree.” If you know anything about PET scans, you know they light up when there’s cancer identified. So that was the point where the doctors said, "There’s nothing left. There are no other approved drugs that we can throw at this. Your only option now is clinical trials."

I had no idea what a clinical trial was. My dad ended up being in multiple.

At first, it felt like he was a lab rat. But he was willing to do anything because it was a chance for him to live longer. I was so deeply uneducated on clinical research at the time, and I just assumed everybody had access to them when traditional treatments stopped working. Now that I’m on the other side of this, I realize how lucky we were to be near a giant health network at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, and that my Dad had incredible health insurance, a supportive job, and an oncologist who was willing to explore clinical trials. We weren’t well off; we were just normal people. But my parents never had to go into medical debt to save his life. And his doctor was so committed to getting my Dad every opportunity to survive. It truly felt like he was ready to die right along with him. We owe him everything.

My Dad went through several trials, each buying us a bit more time. Then, Keytruda hit the market. I remember so vividly his oncologist telling us, “This is it. He's a perfect match for this. This is what we've been waiting for.” The other trials and the chemo were to keep him alive long enough for medicine to advance and get to this point. I remember thinking, “This sounds too good to be true. How can this doctor be so sure?” But I’ve realized that doctors are humans. They’re very smart humans, but they are humans that are just trying to do their best. Unfortunately, there was no improvement for my Dad. The drug did nothing other than make him really sick. That was the last treatment they tried.

It was downhill from there. 2020 came and was horrific in so many ways. They kept looking for options. His oncologist got moved to a new hospital which felt impossible to navigate, and then the pandemic hit. He was trying to get into another trial as he was actively starting to die. Fluid continuously collected in his chest from his lung removal in 2016, and our Mom had to learn how to drain a chest catheter at home so he could breath, due to the pandemic limiting nurses coming into homes.

We had my Dad locked in the house, because COVID would have knocked him out in an instant.

We were really strict with protocols. We had to be. He was so afraid of dying alone. It was horrifying. Along with his stage 4 head and neck cancer, he also suffered from skin cancer and prostate cancer, all in the span of 11 years.

Three months before his death, on a call with his oncologist, my Dad was begging for her to find him another clinical trial. He was skin and bones at this point and nearing hospice care. There was nothing left to do. I said, “Dad, you’re not going to make it. You’re not going to make it through another clinical trial.” But he’d be damned if he didn’t try. He would have moved the sun, moon, and stars to get more time with us.

During the fall of 2020, my boss at the time said, “Go home. Go be with your dad. I don’t care what it takes, go be with him. I’ll handle your work. I’ll handle your clients. I’ll do the thing so you can do what you need to do.” She gave me what no other human could give: the gift of time. I’m indebted to her for this until the day I die.

I temporarily moved home from Idaho. We tried to make him as comfortable as possible as we watched him die.

In December of 2020, three days before his death, we noticed he was sleeping much later than normal. It was odd. When we checked on him, we found him in severe respiratory distress. He was on hospice at the time, so we weren’t supposed to call 911. But he told us to call. He didn’t want to die like that. So we called, they got him to the hospital, and we found out he had pneumonia and sepsis. It was a mess. Hospice told me, “You weren’t supposed to call.” I said, “Well, I’m sorry, but I called. Because that’s what my Dad wanted.”

That night when we called 911 and he went to the hospital, only my mom was allowed with him.

The hospital was under strict covid protocols, as it was December 2020. We all waited with bated breath on that first night he was there. The hospital staff said it was “just pneumonia” and if they could clear it, he could maybe go home. We were so stupidly optimistic. My mom’s best friend is a doctor at that hospital. She wasn’t my Dad’s doctor, but she took my mom aside and said, “He is dying and we need to accept that. You need to get the kids to accept that because he’s never coming home.” I was so mad at her. I remember thinking that she didn’t know him like I did. He was going to come back home. Years later, when I look back on the one photo we have of him in the hospital before he died, anyone could have immediately known he was never coming home. In moments like that, though, you’re delusional and will believe anything you want to believe.

He died two days later of complications from pneumonia, exacerbated by the fact that his body was riddled with cancer. So he passed in December 2020, after 11 years fighting. It’s incredible. Without clinical trials, we would’ve had half that time, maybe less. So that’s what clinical trials did for my family. They gave us time. Time is such a precious resource.

He and I always wrote letters. That was our way.

We both have this thing where when we get emotional, you can hear it in our voice, and we both immediately start crying. So we wrote letters. I wrote him one the day before he died, and the last text message I have from him says, “I read your letter. It was beautiful. I love you so much.” The last letter I have from him was from March of 2020, when he knew he was going to die. He was always referencing life in terms of “I’m not done.” He was 65 when he died, so not terribly young, but not old enough by any means. I guess he just wanted to be more than what the end of his life let him be.

I don’t think we really understood his legacy and how much he left behind until he died. He was so humble. His employer posted about his death and there were hundreds of comments from people we’ve never met. It was an outpouring of love for him. He won five Emmy Awards and you’d never have known it. He never bragged about himself. He worked at the same place for 40 years and to see his legacy after he died, it was beautiful. I’ve thought to myself, why don’t we show people this stuff when they’re alive?

We’re convinced he found peace, because my mom believes he lives on as a blue jay. We don’t have blue jays out here in Idaho, so I always say, “Well, he hasn’t visited me yet!” If I ever see one, I guess we’ll know it’s real. Blue jays are known to be angry birds, and he was always a little angry. We knew he wouldn’t come back as a cardinal! I think he just felt so robbed because even though he survived cancer for 11 years, his life in many ways stopped at 54. I don’t know how you continue on, knowing you have cancer inside of you that’s trying to kill you. So even though he got some extra time, he wanted more.

He became very closed-off. Stoic and not overly emotional. Cancer made him (and all of us) face the fact that he was not superman. He was not not invincible. He’d be angry and cynical when he was sick, then would act normal once he got through treatment. It was as if he was on vacation when he was sick, and then would return the same person we all loved, throwing a ball in the backyard or driving 12 hours to the beach house. I was old enough to know what he was doing, so it was hard to watch. At the same time, though, I wanted my brothers and sisters to have the Dad they deserved. I’ve always said it was his journey. He deserved to live it the way he felt was best, and that's why he put those walls up - to protect us, and himself, too. He wanted to shield his kids from the ugliness as much as he could. It just really hurts because I feel like he died angry. We’d tell him, “You can let go. It’s okay.” We’d beg him to stop treatment. “You don’t need to put your body through this. We love you so much, but you’re suffering.”

I did so much therapy leading up to his death. I knew it was coming.

I told my therapist, “I’m going to therapy my way through this.” She replied, “My dear, you are not going to therapy your way through this.” And she was right. I tried, but to no one’s surprise, it did not work. I needed to feel. I needed to cry when I needed to cry. If I’m going to be living, then I’m going to be feeling. I grieved out loud to anybody who would listen - and not for sympathy, not for pity, but because it is not normalized. It’s taboo to talk about when it shouldn’t be. Why wouldn’t we celebrate these incredible people that we’ve lost too young? Why wouldn’t we want to talk about them? I’m not going to make myself smaller to make you feel comfortable. I’m grieving something that shaped me so fundamentally that I will never be the same person I was before. I am forever shaped by him. Just by knowing him and being loved by him.

Grief is the most holy thing. It happens to most of us, so it’s universal, but nobody goes through it the same way. It’s so unique. I cope really openly. I don’t ever shy away from talking about him. We’re all going to go through grief at some point in our lives, and if one moment of me sharing my pain can signal to someone that I am a safe space for them to grieve, then that’s what I’m going to do.

Grief sneaks up on you, too. A couple months after he died, I found a Walmart receipt from a purchase of two pairs of sweatpants. My Dad was a jeans-at-home kind of guy. You know those guys? Who never wear anything but jeans around the house? He was so uncomfortable as he neared his death and had lost so much weight. So I decided to get him some sweatpants. When I found the receipt, I had been doing really well. I was back to work, felt on top of things, and really felt like I was getting through it. Then all of a sudden I was sobbing on the floor. That’s what grief is: sobbing on the floor at 7:30 in the morning holding a Walmart receipt, because you’ve been transported back there.

I had a weird dream once, and I'm very convinced it was more than just a dream.

My Dad was in it, and he was at peace. He was healed and whole again. He wasn’t riddled with scars from all of the operations. And he was barefoot, which was so weird, because he was never barefoot. We were all sitting on the couch and he opened the door and we were like, “What?? What are you doing here?" And he said, "I just had to come back and let you know that I'm good."

Wherever he is now, that dream is the only thing that has ever made me believe he’s found peace. He never had it here on Earth. He never said things like, "I'll see you on the other side.” His letters would say how proud he was of me and how I'm going to do great things in my life. It was never, “I’m okay with this. I’m at peace with this.” I firmly believe that him showing up in my dreams is his way of telling me, "I'm good now. I know I wasn’t ready for this, but it's great here. You’ll find out some day.”

He still shows up in my dreams every now and then, but only in the background. And that makes sense. He always worked in the background, making magic behind the scenes as a documentary editor. He never wanted the credit (though it was always given because he was so wonderful). He loved sharing the voices of people who felt voiceless. He loved to bridge together depth and light-heartedness, good and evil, and just take something from the camera and make so much more out of it.

I’m proud to share some of the same traits with him. I work really hard to do the right thing and I don't want recognition. I just want to be in the background, making magic happen like he did. I don't want anyone to know that I was involved. I think he drives me to be that way. I don’t know what drove him, though. I wish I had asked. There are so many things that have come up that I wish I had asked. That’s really my only regret. I don’t regret moving or doing what I had to do all those years. But to anyone who's losing someone, ask them everything you could ever think of. And then ask more!

My professional life is now centered around driving access for patients to clinical research.

As I shared earlier, I knew nothing about clinical trials before my dad was in one, and thought that everyone had equal access and opportunity to participate in them. I now work for the Decentralized Trials and Research Alliance (DTRA), an organization focused on increasing access for patients to clinical research through innovative methods, including decentralized options. The FDA defines a decentralized clinical trial as, “A clinical trial where some or all of a clinical trial’s activities occur at locations other than a traditional clinical trial site. These alternate locations can include the participant’s home, a local health care facility, or a nearby laboratory.”

I grew up in a small town, but we were only 30 minutes away from a huge metropolitan city. It was a privilege that we had access to the health system there. This isn’t the case for many folks. Some will say decentralized methods are too much effort or “We only did that because of the pandemic.” There are many more reasons beyond the pandemic! We need to get access to trials for people who aren’t living in predominantly white, affluent communities with big hospital networks.

Everyone deserves a chance to try something that could extend their life. If we can move past the business side of things and get back to the human side of it, we could save more people’s lives. Yes, it takes a lot of work. But we’re doing it: we’re creating the resources, we’re getting all of the smart people together, we’re trying to better educate communities about clinical trials as an option, and we’re going to figure out how to do this. I believe that knowing you have privilege and doing something about it are two very different things.

This experience has taught me that I am so much more capable than I think I am.

I can do really hard things. I can live a good life while still honoring him. I don't have to die just because he did. I can continue to live and have joy. I can live this really great life and still be devastated that he is not here. Two things can be true at once. I trust that time doesn't heal all, but it does make things a whole hell of a lot easier. It does make things possible.”

https://www.devlinfuneralhome.com/obituaries/kevin-p-conrad/